The library of the Institut du Monde Arabe (Arab World Institute) in Paris is home to an extensive collection of writings on music from the Arab world, a region stretching from the Atlas Mountains to the Indian Ocean. This series of blog posts highlights selections from this collection, along with abstracts written by RILM staff members contained in RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, the comprehensive bibliography of writings about music and music-related subjects. From February to November 2024, the Institut du Monde Arabe is hosting the exhibition “Baghdad: A Journey Back to Madinat al-Salam, with Assassin’s Creed Mirage”, showcasing life and achievements in the cosmopolitan city during the golden age of the Abbasid Caliphate. The library is also hosting an on-site exhibition of some of its book holdings covering the history of Abbasid Baghdad.

This craft [singing] is the last craft attained in civilization because it constitutes a luxury and has no occupational role except entertainment and leisure. It is also the first to disappear when a civilization disintegrates and declines.

و هذه الصناعة آخر ما يحصل في العمران من الصنائع لأنها كمالية في غير وظيفة من الوظائف إلا وظيفة الفراغ و الفرح. و هو أيضاً أول ما ينقطع من العمران عند اختلاله و تراجعه.

From Ibn H̱aldūn’s Muqaddimaẗ, chapter 32: On the craft of singing (Fī ṣināʻat al-gināʼ)

Writing in the 14th century, the historian Abū Zayd `Abd al-Raḥman Ibn H̱aldūn (1332–1406) observed musical life as a phenomenon associated with a phase of civilizational development and a sign of civilizational prosperity. Ibn H̱aldūn also observed the evolution of the art of singing in the Islamic caliphates and considered it to have reached perfection during the 8th and 9th centuries in Baghdad, the golden age of the Abbasid Caliphate.

When the second Abbasid caliph, Abū Ğaʻfar al-Mansūr (reign 754–775), envisioned a new city to serve as the capital of the caliphate, he also led the creation of a center of economic prosperity, political power, and intellectual activity that attracted peoples from East and West. Scholars, seekers of knowledge, craftsmen, poets, and musicians flocked to its renowned schools and intellectual and literary circles. Intellectual patronage reached its zenith under Bayt al-ḥikmaẗ (The House of Wisdom), which was established by the caliphate al-Maʾmūn (reign 813–833) in the early 9th century as a center of translation and scientific inquiry. Writings in Greek, Sanskrit, Middle Persian (Pahlavi), Syriac, and others in all fields of knowledge were translated into Arabic.

With political patronage and social acceptance, musicians thrived and scholarly writings on music flourished. Musīqá (music), ġināʼ (singing or the craft of singing), and samāʻ (attentive spiritual listening) became subjects of philosophical discourse and theoretical speculation, topics in adab writings, and contentious issues among jurists, mystics, and religious scholars who discussed at length their permissibility from the perspective of Islamic law.

In the 9th century, a distinctive genre of writing emerged, influenced by Greek theories on music and other scholarly domains that had been translated into Arabic. These writings on music delved into the philosophies of music and music theory. The authors, often philosophers and polymaths, also drew on their practical experiences as instrumentalists, singers, or poets.

The earliest attempt to comment on Greek music theory in Arabic was undertaken by Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn Isḥāq al-Kindī (801?–866?), who served at the Abbasid court under the caliph al-Muʿtaṣim (reign 833–842). Influenced by the writings of Aristotle and his commentators, al-Kindī authored many epistles and introduced the first known, though brief, notation of music written in Arabic. Similarly, Abū Naṣr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Fārābī (870?–950?) was commissioned by the vizier of the caliph al-Qāhir bi-Allāh (reign 932–934) to write his seminal work Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr (The grand book on music). Known as the “Second Teacher”, after Aristotle, al-Fārābī investigated Greek writings on music, adopting some elements and expanding on others. As an ʻūd player, he was able to supplement his writing with commentary on the musical practice of his era. To this day, his book remains one of the most comprehensive works on music theory in Arabic.

Above: A statue of al-Fārābī in central Baghdad, depicted holding a book in his left hand and resting his right hand on the neck of an ʻūd. Photo taken by the author in 2022.

By the 13th century, Ṣafī al-Dīn `Abd al-Mu’min ibn Yūsuf ibn Fāẖir al-Urmawī (1216?–94) continued this tradition of systematization in music theory. He wrote about the modal system that was used then and which was further expanded upon in subsequent centuries. Al-Urmawī also enjoyed the patronage of political courts. He served at the court of the last Abbasid caliph, al-Mustaʻṣim (reign 1242–58) and at the court of the Mongol ruler and invader of Baghdad, Hülegü (1217?–65), who was impressed by the musician’s performance.

By the 13th century, Ṣafī al-Dīn `Abd al-Mu’min ibn Yūsuf ibn Fāẖir al-Urmawī (1216?–94) continued this tradition of systematization in music theory. He wrote about the modal system that was used then and which was further expanded upon in subsequent centuries. Al-Urmawī also enjoyed the patronage of political courts. He served at the court of the last Abbasid caliph, al-Mustaʻṣim (reign 1242–58) and at the court of the Mongol ruler and invader of Baghdad, Hülegü (1217?–65), who was impressed by the musician’s performance.

Above: An illustration of a conversation in medieval Baghdad as depicted by scholar of Medieval Arabic literature, Emily Selove, in her book Popeye and Curly: 120 days in Medieval Baghdad (Moorhead, M.I.: Theran Press, 2021). IMA library reference.

Other depictions and commentaries on musical life are found in writings in poetical, historical, bureaucratic, geographical, and jurisprudence literature, offering valuable insights into the state of music making and status of musicians. Jurists and religious scholars, for example, articulated concerns regarding the classification of sounds into music and non-music, emphasizing the effect of music on behavior and public morality. They debated the effects of listening on the self and its influence on individuals’ relationship to God. Mystics, on the other hand, explored the spiritual preparedness for listening to music and the role of samāʻ in transmitting spiritual knowledge.

Despite the loss of many manuscripts from the period, those that have survived continue to draw scholarly interest and provoke questions regarding the continuity of musical practice and knowledge. The enduring fascination with al-Iṣfahānī’s The book of songs continues to inspire extracts and abridged thematic books on various topics. Musicologists and orientalists have also edited and provided commentaries on medieval Arabic writings to explore the potential influences of these theoretical works on European music theory. These writings not only reflected the intellectual and cultural life of the era but also laid the foundations for musical practices and knowledge that have guided a long lineage of music research and performance in the Islamicate world and beyond.

Written and compiled by Farah Zahra, Associate Editor, RILM

Annotated bibliography

al-ʽAllāf, ʽAbd al-Karīm. قيان بغداد في العصر العباسي والعثماني والأخير (Women singers in Baghdad in the Abbasid and Ottoman periods and beyond) (Baġdād: Dār al-Bayān, 1969). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1969-17952; IMA catalogue reference]

Musical life in the golden period of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–847) was marked by the activities of women slave singers who hailed from different backgrounds and ethnicities and underwent rigorous musical training. The biographies of and anecdotes about 43 women slave singers (qiyān) from that period highlight their role in the court and public life. The fall of Baghdad following the Mongol invasion in 1258 led to a decline in the musical life in the city, a downturn that persisted until the late 19th century, during which women singers became more active, especially in taverns and nightclubs. The first half of the 20th century witnessed a vibrant activity by women singers. Sixty-one women singers from that later period are profiled.

al-Bakrī, ʽᾹdil and Sālim Ḥusayn. قياسات النغم عند الفارابي من خلال كتاب الموسيقى الكبير (Intervals as understood by al-Fārābī in Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr [The grand book of music]) (Baġdād: Wizāraẗ al-Iʽlām, 1975). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1975-28792; IMA catalogue reference].

The chapter Iḥṣā’ al-naġam al- ṭabīʻiyyaẗ fī ālaẗ al-ʻūd from the book Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr (The grand book of music) presents al-Fārābī’s approach to intervals as applied to the ʻūd.

al-Fārābī, Abū Naṣr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad. La musique Arabe. Tome premier: Al-Fārābī–Grand traité de la musique: Kitābu l-musīqī al-kabīr–Livres I et II, trans. by Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1930). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1930-2273; IMA catalogue reference].

Presents a French translation of and commentary on al-Fārābī’s book Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr (The grand book of music).

al-Fārābī, Abū Naṣr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad. كتاب الموسيقي الكبير (Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr [The grand book of music]), ed. by Ġaṭṭās ʻAbd al-Malik H̱ašabaẗ and Maḥmūd Aḥmad al-Ḥifnī (al-Qāhiraẗ: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʻArabī, n.d.). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1967-32301; IMA catalogue reference].

According to al-Fārābī, music is best approached through two branches: the science of theoretical music and the science of practical music. Drawing on Aristotelian logic, issues related to the philosophy of music, such as the first principles of music theory and musical experience, the origin of music and instruments, and the effects of music on the self, among others, are discussed. Aspects of music theory and practice, such as types of intervals, scale systems, elements of rhythm, description and construction of musical instruments, composition, and the types and effects of melodies are analyzed.

al-Fārābī, Abū Naṣr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad and Abū ʻAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʻAbd Allāh Ibn Sīnā. La musique Arabe. Tome deuxième: Al-Fārābī–Livre III du kitābu l-musīqī al-kabīr; Avicenne: Kitābu š-šifāʾ(mathématiques, chap. XII), trans. by Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1935). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1935-2863; IMA catalogue reference]

Presents a French translation of and commentary on al-Fārābī’s book Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr (The grand book of music) and Ibn Sīnā’s book Kitāb al-šifāʾ (The book of healing).

Farmer, Henry George. تاريخ الموسيقى العربية حتى القرن الثالث عشر الميلادي (A history of Arabian music to the 13th century), trans. by Ğurğis Fatḥ Allāh (Bayrūt: Manšūrāt Dār Maktabaẗ al-Ḥayāẗ, 1980). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1980-21512; IMA catalogue reference]

Musical life in pre-Islamic Arabia (1st–6th century), the early Islamic period (632–661), the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), the golden age of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–847), and the periods of decline (847–945) and fall (945–1258) provided a window into the social and cultural contexts of those periods. Political events and the opinion of Islamic jurisprudence scholars on music making and listening shaped the musical life and writings on music of each period. The biographies of famous musicians, singers, instrumentalists, theorists, scientists, and literary scholars are included.

al-Ḥifnī, Maḥmūd Aḥmad. الموسيقى العربية وأعلامها من الجاهلية إلى الأندلس (Arabic music and its masters from pre-Islamic Arabia to al-Andalus) (al-Qāhiraẗ: Maṭbaʻaẗ Aḥmad ʻAlī Muḥaymar, 1951). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1951-7427; IMA catalogue reference]

Music making flourished under the civilizational conditions brought by Islam and through the cross-cultural influence of peoples across the Muslim world in the Middle Ages. The biographies and stories about master musicians from the early Islamic period (610–661), the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), and al-Andalus (711–1492) reflect aspects of the cultural and musical life of the periods.

Ibn H̱urdāḏubaẗ, ʽUbayd Allāh ibn ʽAbd Allāh. مختار من كتاب اللهو والملاهي (Selections from the book Kitāb al-lahū wa-al-malāhī [The book on entertainment and instruments]), ed. by Aġnāṭiyūs ʽAbduh H̱alīfaẗ (2nd ed., rev. and enl.; Bayrūt: Dār al-Mašriq, 1969). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1969-18160; IMA catalogue reference]

The permissibility of singing, music making, and the effect of music and singing on the self was a subject of debate and controversy among Muslim religious scholars. Short biographies and stories about select singers, musicians, and women slave singers (qiyān and ğawārī) from the early Islamic era (632–661), the Umayyad Caliphate (661–750), the early period of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–847) reflect aspects of the musical and cultural life of the periods. Analysis of singing, samāʻ, poetic meters, and rhythmic cycles reveals their rules and aesthetics.

Ibn al-Qaysarānī, Muḥammad ibn Ṭāhir. كتاب السماع (The book of samāʻ), ed. by Abū al-Wafā al-Marāġī (al-Qāhiraẗ: Lağnaẗ Iḥyāʼ al-Turāṯ al-Islāmī, 1994). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1994-35747; IMA catalogue reference]

Prophet Muḥammad’s sayings, stories from the lives of prophets and their companions, and statements by religious scholars provide evidence for the permissibility of singing, listening to music, and samāʻ, thus refuting the arguments of those who opposed permissibility. These opinions are categorized based on different types of samāʻ, including singing, and listening to string instruments, wind instruments, and percussion instruments.

Ibn al-Munaǧǧim, Yaḥyá ibn ʻAlī. رسالة يحيى بن المنجم في الموسيقى (The epistle on music of Yaḥyá ibn ʻAlī ibn al-Munaǧǧim), ed. by Zakariyyā Yūsuf (al-Qāhiraẗ: Dār al-Qalam, 1964). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1964-11109; IMA catalogue reference]

The theory on tones, their types, and intervals as discussed by court musician and music theorist Isḥāq al-Mawṣilī (767–850) provides materials for comparison with ancient Greek philosophers’ theories on the same topics. Al-Mawṣilī’s view on the application of frets on the ʻūd and scales is also a rich addition to music theory. Arabic singing and the construction of melodies reflect the aesthetics and the musical culture of that period.

Iḫwān al-Ṣafā’. رسائل إخوان الصفاء وخلان الوفاء: القسم الرياضي (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity. I: Mathematics) (Bayrūt: Dār Ṣādir, n.d.). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2008-53176; IMA catalogue reference]

Includes the Risālaẗ fī al-mūsīqá (Epistle on music), the fifth epistle of 14 from the first volume on mathematics by Iẖwān al-Ṣafāʼ.

al-Iṣbahānī, Abū al-Faraǧ ʻAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn. أغاني الأغاني: مختصر أغاني الأصفهاني (The songs of songs: An abridged version of Abū al-Faraǧ al-Iṣbahānī’s Kitab al-aġānī [The book of songs]), ed. by Yūsuf ʿAwn and ʿAbd Allāh Al-ʿAlāylī (Dimašq: Dār Ṭalās, n.d., 3 vols.). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2008-53176; IMA catalogue reference]

Presents an abridged version of al-Iṣbahānī’s Kitāb al-aġānī (The book of songs).

al-Iṣbahānī, Abū al-Faraǧ ʻAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn. كتاب الأغاني (The book of songs), ed. by ʻAbd al-Sattār Aḥmad Farrāğ (4th ed.; Bayrūt: Dār al-Ṯaqāfaẗ, 1978, 25 vols.). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1978-23410; IMA catalogue reference]

The transcription and compilation of songs of the courts of the Abbasid caliphs up to Aḥmad al-Muʻtaḍid bi-Allāh (857–902), the courts of the Umayyad caliphs (661–750), and songs from the early Islamic period (610–661), and pre-Islamic Arabia are a way to document the literary, cultural, and political life of those periods. The songs’ texts are accompanied by information about poets, singers, and composers, and analysis and critical commentary of poetic meter, rhythmic cycles, and performance styles. Popular stories and chronicles about caliphs, viziers, rulers, and various people, along with narrations of lineage and tribes supplement the context of the songs. Biographies and chronicles of musicians, poets, singers, and slave women singers served as a rich reference for the entertainment, musical, and literary life during the first three centuries of the medieval Muslim world.

al-Kindī, Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn Isḥāq. رسالة الكندي في خبر صناعة التأليف (The epistle of al-Kindī Risālaẗ fī ẖabar ṣināʽaẗ al-taʼlīf [The epistle on the craft of composition]), ed. by Yūsuf Šawqī (al-Qāhiraẗ: Dār al-Kutub al-Miṣriyyaẗ, 1996). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1996-42433; IMA catalogue reference]

Intervals, tuning, scales, octaves, tetrachords, types of tonal structures and construction of modes, modulation and transition, and the relationship between rhythmic cycles, poetic meter, and music are analyzed.

al-Kindī, Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn Isḥāq. مؤلفات الكندي الموسيقية (The musical writings of al-Kindī), ed. by Zakariyyā Yūsuf (Baġdād: Maṭbaʽaẗ Šafīq, 1962). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1962-9228; IMA catalogue reference]

Introduces editions of five epistles on music written by al-Kindī: Risālaẗ fī ẖabar ṣināʻat al-taʼlīf, Kitāb al-muṣawwitāt al-watariyyaẗ min ḏāt al-watar al-waḥīd ʻilá ḏāt al-ʻašarat awtār, Risālaẗ fī ağzāʼ ẖabariyyaẗ fī al-mūsīqá, Muẖtaṣar al-mūsīqá fī taʼlīf al-naġam wa-sunʻaẗ al-ʻūd, and al-Risālaẗ al-kubraẗ fī al-taʼlīf.

al-Nağmī, Kamāl. يوميات المغنين والجواري: حكايات من الأغاني (Chronicles of singers and women slave singers: Stories from Kitāb al-aġānī [The book of songs] of Abū al-Farağ al-Isbahānī) (al-Qāhiraẗ: Dār al-Hilāl, 1986). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1986-30654; IMA catalogue reference]

A selection of 27 stories from Kitāb al-aġānī (The book of songs) about the lives of women and men musicians and singers.

Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī. رسالة نصير الدين الطوسي في علم الموسيقى (The epistle of Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī on music theory), ed. by Zakariyyā Yūsuf (al-Qāhiraẗ: Dār al-Qalam, 1962). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1964-11108; IMA catalogue reference]

Music should be studied as two branches: the science of composition (taʼlīf) and the science of rhythm (īqāʻ). Intervals and their types, and what makes plausible intervals and tones, are important topics in music theory.

Nielson, Lisa. Music and musicians in the medieval Islamicate world: A social history (London: I.B. Tauris, 2021). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2021-96979; IMA catalogue reference]

During the early medieval Islamicate period (800–1400), discourses concerned with music and musicians were wide-ranging and contentious, and were expressed in works on music theory and philosophy as well as literature and poetry. In spite of attempts by influential scholars and political leaders to limit or control musical expression, music and sound permeated all layers of the social structure. A social history of music, musicianship, and the role of musicians in the early Islamicate era is presented. Focusing primarily on Damascus, Baghdad, and Jerusalem, it draws on a wide variety of textual sources–including chronicles, literary sources, memoirs, and musical treatises–written for and about musicians and their professional and private environments. The status of slavery, gender, social class, and religion intersected with music in courtly life and reflected the dynamics of medieval Islamicate courts. [Adapted from the book synopsis]

Saʿīd, H̱ayr Allāh. مغنيات بغداد في عصر الرشيد وأولاده من “كتاب الأغاني” و غيره (Women singers in Baghdad during the reign of the caliph Hārūn al-Rašīd and his sons as depicted in Kitāb al-aġānī [The book of songs] and other books) (Dimašq: Wizāraẗ al-Ṯaqāfaẗ wa-al-Iršād al-Qawmī, 1991). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1991-37910; IMA catalogue reference]

Musical life in the first period of the Abbasid Caliphate was vibrant. During this period, singing and music making became a profession. Under the rule of Hārūn al-Rašīd and his sons (8th–9th century), some women slaves, known as the qiyān, were acquired, trained, and encouraged to be professional singers at the palace. The music scene of the qiyān musical activity was not limited to the Abbasid court as they also performed at taverns and homes of elite circles in Baghdad. Stories about the qiyān narrated by various scholars reflect the social norms in Abbasid Baghdad and attest to the qiyān’s mastery of poetry, wit, and talent. The biographies of five qiyān are included.

Saʿīd, H̱ayr Allāh. “مجتمع بغداد الغنائي في العصر العباسي” (Musical life in Abbasid Baghdad), al-Mawqif al-adabī 264 (Nīsān 1993) 59–67. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1993-31671; IMA catalog reference]

Musical life in Abbasid Baghdad flourished both in the political court and the city. Singers and musicians lived under the patronage of caliphs and were organized into ranks. Notable musicians of that era included Isḥāq al-Mawsilī, Ibrahīm al-Mawsilī, Manṣūr Zalzal al-Ḍārib, and Ibn Ǧāmiʻ. This period also saw the development of elaborate performance styles and etiquette. The residents of Baghdad also engaged in music and singing on various occasions, with performances occurring in taverns and in domestic and public spaces throughout the city.

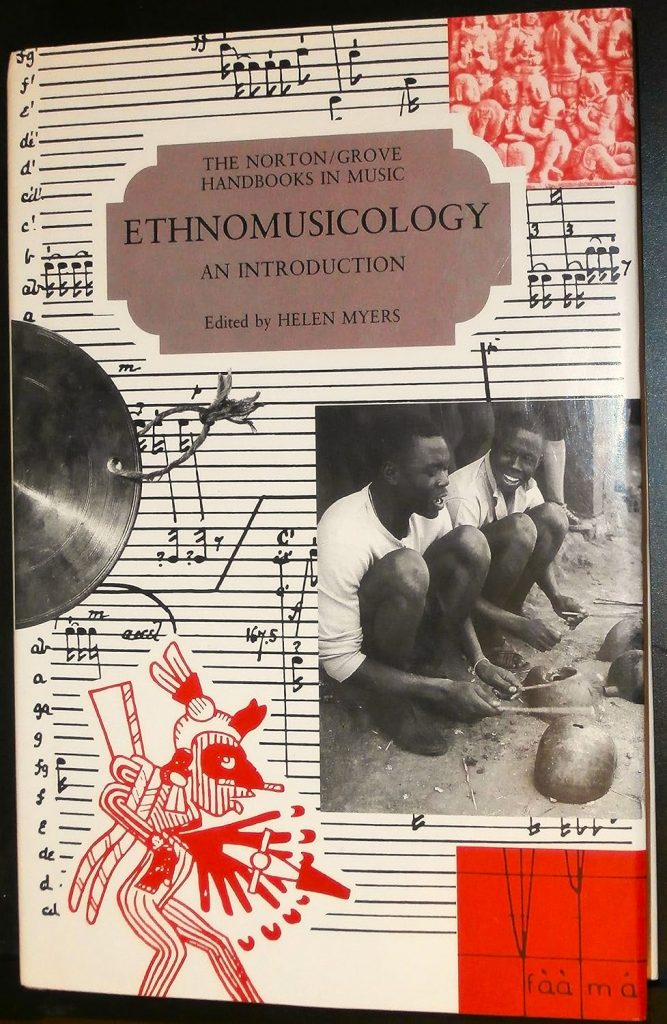

Shehadi, Fadlou. Philosophies of music in medieval Islam (Leiden: Brill, 1995). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1995-9473; IMA catalogue reference]

The philosophies of music and music theory in the medieval Muslim world were formulated in works by al-Kindī, al-Fārābī, Iẖwān al-Ṣafāʼ, Ibn Sīnā, al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad ibn `Alī al-Kātib, and Ibn ʻArabī. In the same period, various perspectives on the permissibility of music making, listening, and samāʻ were advanced by Muslim religious scholars such as Ibn Taymiyyaẗ, al-Ġazālī, Ibn ʿAbd Rabbih, and Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Ġazālī.

Šihāb, Ġādaẗ Anwar. موسوعة الموسيقى والغناء في العصر العباسي مع أشهر الموسقيين والمؤلفين والمغنين والمغنيات (Encyclopedia of music, singing, composers, musicians and men and women singers in the Abbasid period) (Bayrūt: al-Dār al-ʽArabiyyaẗ li-l-Mawsūʽāt, 2012). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2012-50363; IMA catalogue reference]

During the rule of the Abbasids in Baghdad, music making was significantly influenced by the Abbasid caliphs’ positive attitudes towards music. Their encouragement and financial support for musicians and singers led to the specialization of musical arts and the emergence of a musician class within the Abbasid palace and society. The popular music and singing genres of the time were performed in various contexts, from the palace to private homes and taverns. Slave markets played a pivotal role as sources of women slave singers, who underwent rigorous training to master singing or instrument playing. These women gained empowerment as a social class, influencing the social and political life of the caliphate. The period was also marked by the evolution of musical instruments, with significant refinements in the making and performance of wind, percussion, and string instruments. Biographies and chronicles of women and men musicians and singers highlight their contributions and the social life of the time. The genres of poetry and their forms were closely linked to rhythmic cycles, with Persian poetry notably influencing Arabic poetry. Muslim scholars and jurists contributed to the discourse on the permissibility of singing and music within samāʻ. The practice of samāʻ by the Sufis played a crucial role in the spiritual life of the community, leaving a lasting impact on the consolidation of Sufi samāʻ forms that influenced centuries of practice across the Muslim world.

Sawa, George Dimitri. Music performance practice in the early ʿAbbāsid era 132–320 AH/750–932 AD (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1989). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1989-35195; IMA catalogue reference]

Two medieval writers with access to extant repertoire and practices, and to written and oral information on music literature and theory, critically and thoroughly covered the subject of music making and music theory in the medieval Middle East. Al-Fārābī (872?–950?), a performer and theorist, systematized musical practices according to Greek models in Kitāb al-mūsīqá al-kabīr (The grand book of music), and the recently discovered Kitāb iḥşā’ al-īqāʿāt (The book for the basic comprehension of rhythms). The historian, poet, and storyteller al-Iṣbahānī (897–967) compiled anecdotes on musical practices in Kitāb al-aġānī (The book of songs). Analysis of specific performances reveals the physical, verbal, and social behaviour of both musicians and audience; the textual and modal relationship between songs; and the textual, musical, and extra-musical criteria for performance excellence. (synopsis by the author)

al-Urmawī, Ṣafī al-Dīn ʻAbd al-Muʼmin ibn Yūsuf ibn Fāẖir. La musique Arabe. Tome troisième: Ṣafiyu-d-Dīn al-Urmawī–I. Aš-šarafiyyah ou épître à šarafu-d-dīn. II. Kitāb al-adwār ou livre des cycles musicaux, ed. by Christian Poché and trans. by Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger (Paris: Paul Geuthner, 1938). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1938-2680; IMA catalogue reference]

Presents a French translation of and commentary on Ṣafī al-Dīn al-Urmawī’s epistle on music al-Risālaẗ al-šarafiyyaẗ fī al-nisab al-taʼlīfiyyaẗ (The epistle on musical proportions) and his book Kitāb al-adwār (The book of cycles).

al-Urmawī, Ṣafī al-Dīn ʻAbd al-Mu’min ibn Yūsuf ibn Fāẖir. كتاب الأدوار في الموسيقى (Kitāb al-adwār fī al-mūsīqá {The book of cycles]), ed. by Ġaṭṭās ʻAbd al-Malik H̱ašabaẗ (al-Qāhiraẗ: al-Hayʼaẗ al-Maṣriyyaẗ al-ʽĀmmaẗ li-l-Kitāb, 1986). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1986-30625; IMA catalogue reference]

Topics of music theory analyzed include: the explanation of tones and their types, the division of frets, the relationship of intervals, the causes of dissonance and consonant combinations, the relationships between cycles, the arrangement of two strings, accompaniment and performance of modes on the ‘ūd, the most common modes, the similarities between notes, transposed cycles, scordatura, rhythmic cycles, and the effects of the modes.

Yūsuf, Zakariyyā. “موسيقى الكندي: ملحق لكتاب “مؤلفات الكندي الموسيقية (Music of al-Kindī: An annotation to the book Muʼallafāt al-Kindī al-mūsīqiyyaẗ [al-Kindī’s writings on music]) (Baġdād: Maṭbaʽaẗ Šafīq, 1962). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1962-9227; IMA catalogue reference]

Al-Kindī’s nine epistles in music approached music from five perspectives: sonic and structural, temporal and rhythmic, psychological, medical, and astronomical. It is an appendix to the book Muʼallafāt al-Kindī al-mūsīqiyyaẗ (al-Kindī’s writings on music) on al-Kindī’s theoretical writings, abstracted as RILM 1962-9315.