The library of the Institut du Monde Arabe (Arab World Institute) in Paris is home to an extensive collection of writings on music from the Arab world, a region stretching from the Atlas Mountains to the Indian Ocean. This series of blog posts highlights selections from this collection, along with abstracts written by RILM staff members contained in RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, the comprehensive bibliography of writings about music and music-related subjects. In 2026, the Institut du Monde Arabe will host an exhibition on wedding cultures in the Arab world, and the institute’s library will hold an on-site exhibition of its book collection covering this topic.

In the Arab world, weddings unfold through a series of ceremonies where daily preparations and references to the sacred intertwine to initiate and bless the union of two families. From the first promises of the engagement ceremony to the morning after the wedding night, each step is guided by social norms and enveloped in society’s ideals of generosity, community, and gender roles. Whether it takes place in a single day or over the traditional seven days, each step of the wedding is intentionally marked by specific melodies, rhythms, and sounds. Prior to the actual wedding ceremony, during the night of ḥinnaẗ, natural dye is applied to the bride’s hands and feet as women praise the her beauty and recount love’s woes in song. Then, joyous zaġārīd (trills) through the air to declare the news to all, near and far, as the cantillation of the Qur’an or other sacred prayers proclaims the couple’s union in front of God. As upbeat drums of the zaffaẗ announce and accompany the procession of the newlyweds, a subtler percussion chimes from the ẖilẖāl, the bride’s anklet, gifted from the groom to the bride to honor her femininity. These sounds intertwine with the most refined cultural expressions–skillfully crafted jewelry, intricately embroidered adornments, fragrances, and the finest cuisine, all blended together in celebration.

Even as the rush of modern life permeates every aspect of society in the Arab world, weddings continue to preserve many of the age-old customs. The related ceremonies create a momentary pause in the relentless flow of life to mark new social bonds and a transformation from singularity to family. The writings and research related to this lifecycle event covered in the annotated bibliography below explore the enduring customs across various regions of the Arab world: from the Tuareg tribes of the Sahara Desert and the Nubian tribes of the Nile Valley to urban dwellers in Cairo and Mosul. They document lyrics, transcribe melodies, describe instruments, and detail the roles of men and women in musical performances–all in an ongoing effort to understand and preserve this rich heritage of wedding customs and music.

Annotated bibliography

ʿAlī, Muḥammad Šiḥātaẗ. أغاني النساء في صعيد مصر: الأعراس، البكائيات، التحنين [Women’s songs in Upper Egypt: Wedding, lament, and pilgrimage songs] (al-Qāhiraẗ: al-Hayʾaẗ al-Miṣriyyaẗ al-ʿĀmmaẗ li-l-Kitāb, 2015). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2015-92222; IMA catalogue reference].

Transcribing orally transmitted songs in Upper Egypt is crucial, especially as many of them are at risk of being forgotten due to the passing of older women who have memorized them. Song texts were collected as the result of ethnographic research in villages in the al-Badārī province of the Asyut governorate. The three main categories of the transcribed repertoire are songs related to rites of passage, such as weddings and their associated ceremonies, funeral and lament songs known as bukāʾiyyāt, and songs known as taḥnīn, performed in preparation for the pilgrimage. An appendix with photos capturing women’s activities in various aspects of life, including domestic chores, agricultural work, food preparation, and market activities is included.

ʿArnīṭaẗ, Yusrá Ǧawhariyyaẗ. الفنون الشعبية في فلسطين [Popular arts in Palestine] (Rāmallāh: Dār al-Šurūq li-l-Našr wa-al-Tawzīʿ, 2013). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2013-54151; IMA catalogue reference]

The tangible and intangible forms of folklore–encompassing popular musical expressions, embroidery customs, and ceremonial practices associated with marriage and celebrations–serve as testimony to the enduring heritage and cultural continuity of the Palestinian people. The present effort to document select aspects of Palestinian folklore serves several purposes: first, to safeguard these manifestations of popular culture and ensure their continuity; second, to forge a robust connection between the present and history; third, to uncover the creative dimensions inherent in Palestinian folklore; and ultimately, to inspire fellow researchers in music and the arts to undertake similar endeavors in documenting Palestinian folklore. Folk songs should be approached with the same urgency to study and preserve such as other Palestinian traditions. Popular songs’ characteristics are detailed, including the characteristics of colloquial dialects, the melodic content, maqam structure, ornaments, and more. Transcriptions of the melodies of 66 songs, along with their transcribed lyrics, are included and are chosen as hailing from different cities. The songs are grouped by topic or occasion, as follows: children’s songs and lullabies, songs of religious holidays and celebrations; love and wedding songs; songs of war and encouragement; work songs; drinking, satirical, and political songs; dance songs; funeral chants and laments; songs of stories and tales. Popular song is a reflection of the Palestinian peoples’ ways of life and social customs and is a spontaneous expression of collective feelings and aspirations.

al-ʿĀṣimī, Ğamīlaẗ. أغاني نساء مراكش: اللعابات، الطقيطقات، الهواري، التهضيرة [Women’s songs in Marrākuš: The laʿābāt, the ṭaqīṭaqāt, the hawārī, and the tahḍīraẗ] (Marrākuš: Muʾassassaẗ Āfāq li-l-Dirāsāt wa-al-Našr wa-al-Ittiṣāl, 2012). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2012-50441; IMA catalogue reference].

Women’s songs in Marrākuš are transmitted orally from one woman to another, they are unauthored and composed collectively. Based on fieldwork with professional women performers, song forms and texts are transcribed alongside documentation on the accompanying percussion instruments and the names of the women’s groups performing each piece. Twenty-four song texts from the laʿābāt, a women’s ensemble that performs during weddings and related ceremonies, are included. Additionally, 20 song texts of the ṭaqīṭaqāt, a song form that is also performed by the laʿābāt groups on festive occasions and features articulate lyrics and steady rhythms, are transcribed. Twenty-nine song texts from two types of the hawārī song form are included, and 11 song texts of the tahḍīraẗ form, performed by groups of women during weddings, promenades, or private gatherings, are presented. An appendix contains 12 transcriptions of short excerpts from songs and the notation for each percussion section of the two hawārī song forms.

al-Asyūṭī, Darwīš. أفراح الصعيد الشعبية: من طقوس ونصوص احتفاليات الزواج والحمل والولادة والختان [The weddings of Upper Egypt: Rituals, texts, and ceremonies of marriage, pregnancy, and circumcision] (al-Qāhiraẗ: al-Hayʾaẗ al-Miṣriyyaẗ al-ʿĀmmaẗ li-l-Kitāb, 2012). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2012-52032; IMA catalogue reference].

Describes the rituals and customs associated with engagement and marriage preparation in Asyut, Upper Egypt. It covers various traditions, including the dowry presentation, the shopping process for establishing a new bridal household, the ḥinnaẗ night for the bride, and the ritual shower for the groom, among other related ceremonies. It also includes transcriptions of song lyrics collected from narrators in Asyut, as well as others memorized by the author.

Bayrūk, ʿAzzaẗ. الغناء الحساني بين التنظيم والتلقائية [Hassanian singing between structure and spontaneity] (al-Rabāṭ: Markaz al-Dirāsāt al-Ṣaḥrāwiyyaẗ/Centre des Études Sahariennes, 2015). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2015-92229; IMA catalogue reference].

The singing of the Ḥassānī tribes can be categorized into two branches: structured singing, also known as the hūl, which has been shaped by the influences of Arab, African, and Berber traditions and developed during the Ḥassānī rule in the Western Sahara during the 15th and 16th centuries; and a second branch that is unstructured and spontaneous, encompassing prophetic praise, wedding songs, rain songs, work songs, and lullabies, among others. The analysis includes a selection of song texts and their social contexts.

al-Daywahǧī, Saʿīd. تقاليد الزواج في الموصل [Marriage traditions in Mosul] (al-Mawṣil: Muʾassasaẗ Dār al-Kutub, 1975). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1975-28979; IMA catalogue reference].

Explores the social customs associated with marriage in Mosul, from the etiquette of selecting a bride or groom to the week-long wedding celebrations and the social norms governing interactions between the families of the bride and groom. Transcriptions of the lyrics of 32 wedding songs are included. Thematically, these songs celebrate the bride and groom, describe their virtues and beauty, express the families’ emotions as they bid farewell to their daughters and sons, and highlight societal expectations of marriage, among other topics.

El Mallah, Issam. The role of women in Omani musical life/Die Rolle der Frau im Musikleben Omans (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1997). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1997-11646; IMA catalogue reference].

The role of women in the transmission and preservation of Omani traditional music is significant, as is their influence. Women take on roles as singers, drummers, dancers, instrumentalists, and leaders in organizing dance and singing groups. The participation of women in musical arts can be grouped into two categories: arts exclusively practiced by women and those practiced alongside men. The ones involving men and women include collective dance, collective drumming, and work songs. The art forms exclusively practiced by women include women’s drumming circles, women’s work songs, Bedouin dances, wedding songs and dances, traditional healing ceremonies, and arts involving young girls. A description of the setting and context of each art form is included.

Ibn Ḥarbān, Ǧāsim Muḥammad. الزواج في المجتمع البحريني عاداته، تقاليده، فنونه [Marriage in Bahraini society: Customs, traditions, and arts] (Bayrūt: al-Muʾassasaẗ al-ʿArabiyyaẗ li-l-Dirāsāt wa-al-Našr, 2000). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2000-84970; IMA catalogue reference].

Weddings in Bahrain involve a wealth of cultural expressions. The process of marriage includes various customs such as dowry arrangements and the elaborate preparation of both the groom and the bride. There are specific dress codes for men and women, along with jewelry, embellishments, and perfumes designated for each. The food prepared for weddings is also central to the ceremony. Women musician ensembles known as the ʿiddaẗ typically perform at these events. The song forms and accompanying dances, including the dizzaẗ and the zaffaẗ, are described, along with the rhythms and percussion instruments used. Related arts and customs are also discussed, such as the practice of naḍir–a ritual where individuals offer physical or symbolic gifts in hopes of fulfilling a wish or prayer; the ʿāšūrī which involves women performing drums and dance ceremonies; the ẖammārī, a women’s dance where participants are covered with a body cloth; and the naǧdī mawwāl, a song form sung by women, among other events. Transcriptions of some song texts and rhythms are included.

Mahfoufi, Mehenna. Chants de femmes en Kabylie: Fêtes et rites au village–Étude d’ethnomusicologie [Women’s songs in Minṭaqaẗ al-Qabāʾil: Celebrations and rites in the village–An ethnomusicological study]. (Paris: Ibis Press, 2005). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2005-16247; IMA catalogue reference].

A study of village song in Minṭaqaẗ al-Qabāʾil, focusing on the songs of women that accompany various festivals and the rhythm of daily life: birth, marriage, the expression of love, lullabies, bouncing (a game that consists of bouncing babies on one’s lap), death, and religious song. The songs are transcribed and translated, and their musical form is described and analyzed. The accompanying CD features wedding songs in tracks 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13.

Mécheri-Saada, Nadia. Musique touarègue de l’Ahaggar (sud algérien) [Tuareg music of the Ahaggar in southern Algeria] (Paris: Awal; Paris: L’Harmattan, 1994). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1995-9971; IMA catalogue reference].

The Ahaggar in southern Algeria is the homeland of Tuareg culture. Tuareg music is linked to the context of its performance, notably village festivals. Principal Tuareg instruments include the imzad (one-string fiddle), the tazamar (end-blown flute), and drums. Five musical genres are differentiated, including women’s marriage songs (āléwen) and the chanted poetry accompanied by drums, the tindé. The music’s texts, their themes, their social significance, and their poetics are analyzed.

Kamāl, Ṣafwat. “أفراح النوبة” [The weddings of the Nubia], al-Funūn al-šaʿbiyyaẗ 100 (yanāyir-dīsambir, 2015) 51–75. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2015-92886; IMA catalog reference].

In Nubia, marriage involves customs and rituals ranging from the engagement period to the ḥinnaẗ night in preparation for the wedding, the offering of a dowry, a feast on the wedding day, and the exchange of gifts, among others. The celebrations typically last for seven days. Transcriptions of selected songs that accompany these rituals were collected before the displacement of the Nubian peoples following the building of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s and thus highlight traditional Nubian social values and religious beliefs.

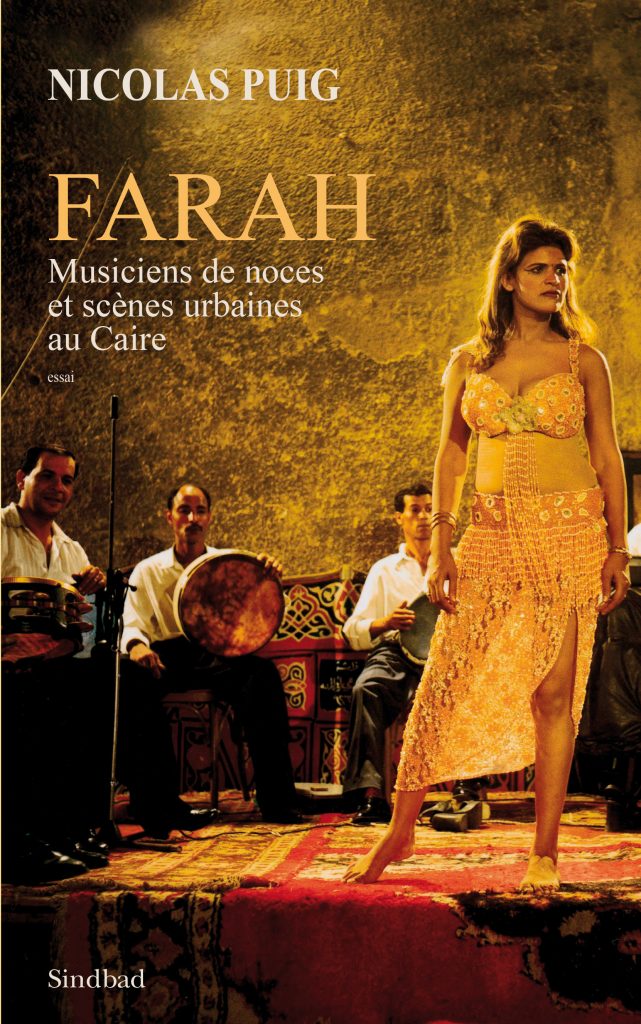

Puig, Nicolas. Farah: Musiciens de noces et scènes urbaines au Caire (Arles: Actes Sud, 2010). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2010-54197; IMA catalogue reference].

Faraḥ, which literally means joy or happiness, refers to the wedding ceremonies and street festivities in Egypt. Vibrant wedding nights, featuring musical ensembles, dancers, and many forms of socialization reflect social class and status. Musicians’ and singers’ negotiation of social norms and perceptions is approached as social performance. A proper understanding of marriage festivities in urban spaces is situated within the evolving attitudes towards public urban areas in Cairo, and in relation to other local festivities such as festivals and the celebration of saints’ mawlid. Since the mid-19th century, the modernizing reforms of public urban spaces have significantly influenced the venues for public music-making in Cairo, leading to changes in musical forms, the introduction of new instruments, and the adoption of new technologies. These changes have, in turn, affected the form and delivery of music during street weddings. A closer examination of the lives and work of four wedding musicians illustrates the numerous economic and social factors that shape their careers, their aspirations, and the challenges they encounter as wedding musicians in Cairo.

Written and compiled by Farah Zahra, Associate Editor, RILM

Related Bibliolore posts:

https://bibliolore.org/2024/09/07/writing-on-music-in-abbasid-baghdad-an-annotated-bibliography/

https://bibliolore.org/2024/07/12/palestine-in-song-an-annotated-bibliography/