Virgil Thomson first met Gertrude Stein in the winter of 1925–26. Early in 1927 he asked her to write an opera libretto, and the plans for Four saints in three acts began to take shape; the text was completed in June of that year and the music was finished in July 1928.

The opera concerns two Spanish saints, Teresa of Ávila and Ignatius of Loyola, who are surrounded by groups of young religious figures. In fact the work has four acts and over 30 saints. A compère and commère introduce the characters and announce the progress of the action. The strangely haunting and at times repetitive poetry of Stein is declaimed by the singers in a musical language derived from many sources, including Gregorian and Anglican chant, children’s songs, and Sunday School hymn singing, with a harmonious accompaniment for small orchestra. Although the setting of the words is deceptively simple and direct, there are considerable subtleties in the music to parallel the implied imagery of the words.

Four saints in three acts was first heard in Hartford, Connecticut, in February 1934, produced by an organization called the Friends and Enemies of Modern Music. When the production moved to New York City it created theatrical history with its all-black cast. The opera received over 60 performances within a year, and Thomson’s reputation was made almost overnight.

This according to “Thomson, Virgil Garnett” by Neil Butterworth (Dictionary of American classical composers, 2nd ed. [Abington: Routledge, 2005] pp. 456–59); this resource is one of many included in RILM music encyclopedias, an ever-expanding full-text compilation of reference works.

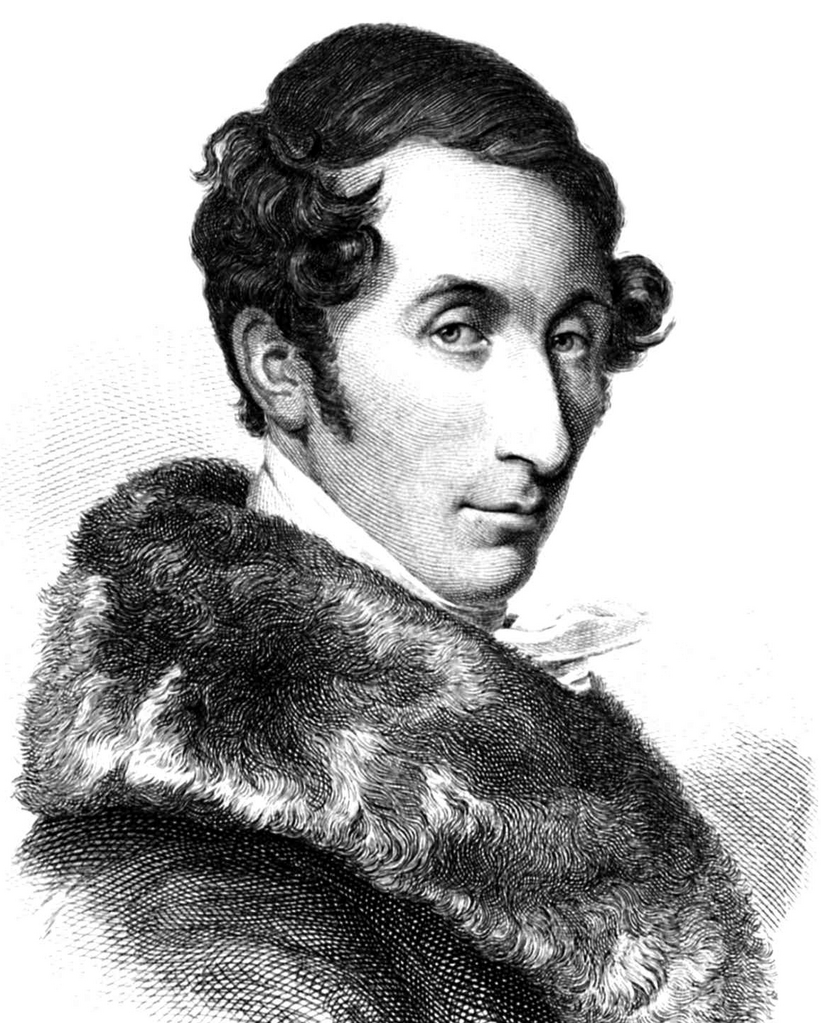

Today is Thomson’s 120th birthday! Above, the 1934 New York production; below, the opening of Mark Morris Dance Group’s 2006 production.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JKKWfbweeMw]

BONUS: A brief documentary with archival footage from 1934, including the voice of Gertrude Stein.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXINp5iuUyw]