The Indian singer Jayashri Ramnath (better known as Bombay Jayashri) was introduced to Karnatak music in her early childhood, influenced by her parents’ roles as music teachers. Jayashri began her performing career at the age of 28, and having grown up in cosmopolitan Mumbai (formerly Bombay), she was exposed to a wide range of music genres, including bhajans, film music, Hindustani classical, and light music. Despite this diverse musical background, Jayashri’s passion for Karnatak music remained at the core of her identity. During her childhood and college years, she kept her Karnatak training a secret while also exploring other musical opportunities, including singing jingles. Her voice, shaped by Hindustani training, combined with her soulful delivery drawn from her eclectic musical experiences, made Jayashri a distinctive performer.

Jayashri also has ventured into other genres, frequently collaborating with a variety of instrumentalists and vocalists. Boldly, for a Karnatak classical singer not yet widely established, she sang for films in multiple South Asian languages, including Hindi, Malayalam, Tamil, Kannada, and Telugu. Many of these film songs became huge successes, earning her the title of best female playback singer in Tamil Nadu province. Until today, her music is characterized by a contemplative quality known as sruti suddham. Initially criticized for offering sweet music rather than more profound depth, Jayashri’s style has matured into a serene and resonant presence. Her stage demeanor exudes dignity, free from unnecessary gestures, reflecting her deep connection to the beauty of raga. As a composer, she has also earned recognition for her collaborations with artists like Chitra Visweswara, Parvathy, and others.

The most exceptional aspect of her musical career, however, is her immense popularity, which spans across regions and extends worldwide. She has truly become an internationally beloved star, forging a unique connection with diverse audiences through her hypnotic and compelling voice. Beyond her musical talents, she is known for her warmth and kindness in post-concert interactions, leaving lasting memories not only of her remarkable music but also of her humble and genuinely kind nature.

This according to “Bombay Jayashri Ramnath–Notes of resilience: Reflecting with grace and gratitude” by Shailaja Khanna (Sruti: India’s premier magazine for the performing arts 31/1 [2024] 20–25; RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2024-10526). Find it in RILM Abstracts with Full Text.

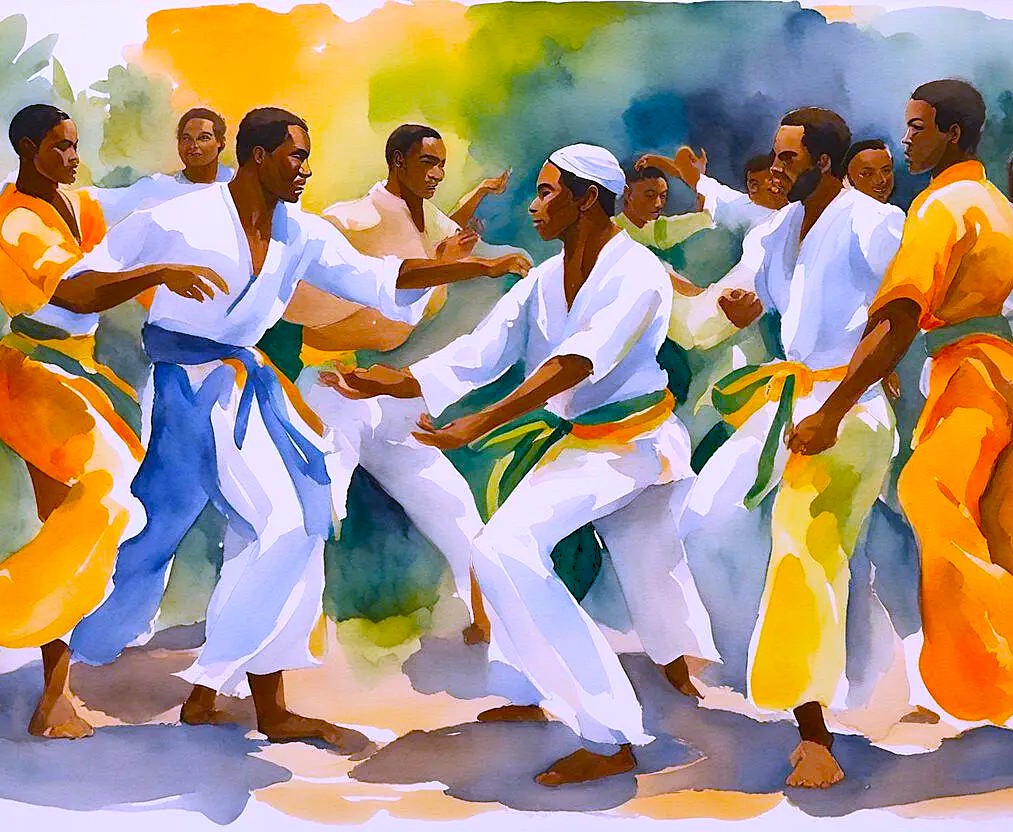

Below, Jayashri performs at a concert in Sri Lanka.