Music plays a vital yet rarely noticed role in political ads, as explored by Jason Lee Oakes in “Obama’s One chance: Winning over hearts and ears” (IASPM-US 16 May 2012). Applying musicological analysis to several campaign advertisements—including President Obama’s controversial ad focused on the killing of Osama Bin Laden under his command—Oakes considers how musical techniques are used to provoke emotional responses to political issues, or to create issues where none formerly existed.

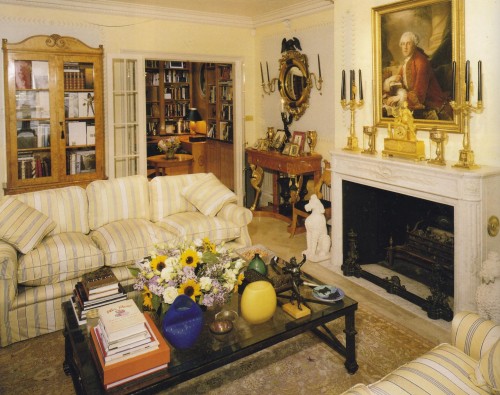

Below, the advertisement in question. Above, the first U.S. presidential campaign song, which circulated as a broadsheet during the successful 1824 campaign of Andrew Jackson (click to enlarge).

Related article: 9/11 music