Scrabble™-to-MIDI is a computer-emulated two-dimensional board game that generates MIDI music as the game is played.

The plug-in translator and its configuration parameters comprise a composition. Improvisation consists of playing a unique game and of making ongoing adjustments to mapping parameters during play.

Statistical distributions of letters and words provide a basis for mapping structures from word lists to notes, chords, and phrases. While pseudo-random tile selection provides a stochastic aspect to the instrument, players use knowledge of vocabulary to impose structure on this sequence of pseudo-random selections, and a conductor uses mapping parameters to variegate this structure in up to 16 instrument voices.

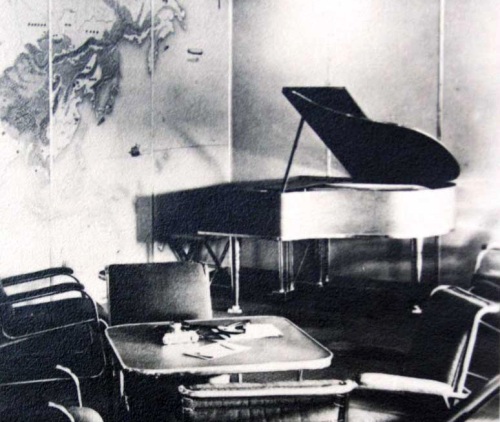

This according to “Algorithmic musical improvisation from 2D board games” by Dale E. Parson, an essay included in ICMC 2010: Research, education, discovery (San Francisco: International Computer Music Association, 2010). Above, a demonstration of Scrabble™-to-MIDI.

Related articles: