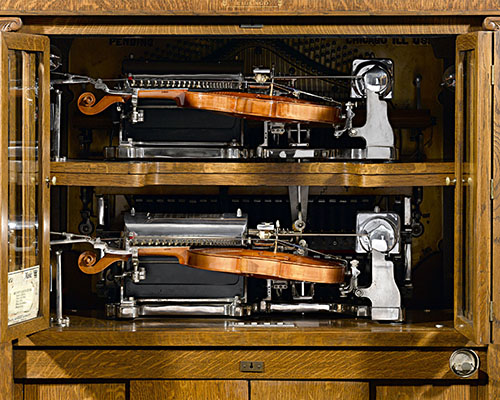

Nobody knows how many of the 2,500 violano virtuosos manufactured by the Mills Novelty Company between 1912 and 1926 exist today, but one ended up in the Smithsonian Institution in 1959, where it was designated one of the eight greatest inventions of the decade.

A complex instrument, it contains a 44-note piano with bass strings in the center and treble notes on either side in addition to a real violin. An electric motor with variable speeds simulates the action of bowing through the use of electromagnets.

Arthur Sanders, a specialist in mechanical instruments, was engaged to oversee the instrument’s restoration. “I assumed theirs had been in operating condition when they got it,” Sanders later noted, “but the grease had jelled, the oil had become gummy, and it needed new strings.” Mr. Sanders worked on it with some spare parts from similar instruments. “Even the curators from the fossil section came around,” he said, describing what must have been an exciting moment for the famous museum.

This according to “Making music with machines” by James Feron (The New York times 17 June 1984, pp. 507, 529). Above and below, the rare double violano virtuoso.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ScipR0fqWeE]