Folkways Records, now Smithsonian Folkways, turns 70 this month! The son of Moses Asch, the company’s founder, tells the story:

“When my father founded Folkways Records in 1948, it was his third record company. The first was Asch Records founded in the 1930s, on which he released the first recordings of Lead Belly.”

“The second was Disc Records, founded during World War II….While initially a success, Disc went bankrupt in 1947 when, as my father told me, he lost the anticipated Christmas sales due to a snowstorm in mid-December that delayed the release of a Nat King Cole Christmas album until after December 25th.”

“Moe started Folkways with a loan of $10,000 from his father and the goodwill of his assistant, Marian Distler, who agreed to be the ‘front’ person so that he could get going while still under bankruptcy.”

“In calling the company Folkways, a term that connotes recognition of and respect for the diversity of traditions that exist in the world, my father located himself as standing against those who sought to limit what was available in the market place to cultural expressions that conformed to the tastes and values of white, middle-class America as defined by Red Scare ideologues.”

“Put more broadly, Folkways represented a place where voices, otherwise silenced not only by political considerations but also by an economic system intent on maximizing profits to the exclusion of all else, could be heard. Hence, his proviso that he generally did not take on projects he thought had great commercial potential but gave serious consideration to worthy projects that, nevertheless, promised little commercial success.”

Quoted from “Folkways Records and the ethics of collecting: Some personal reflections” by Michel Asch (MUSICultures XXXIV–XXXV [2007–2008] pp. 111–27).

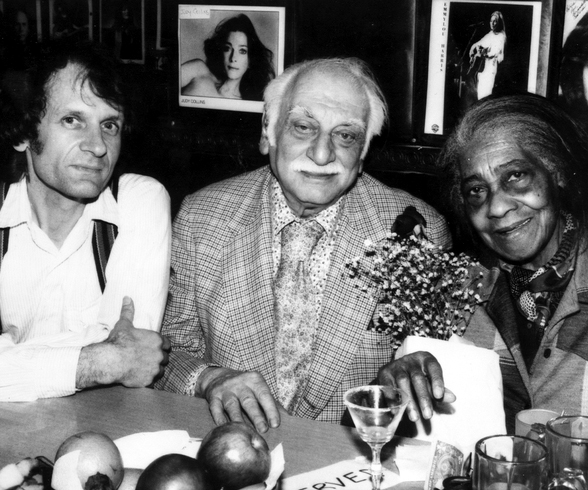

Above, Moses Asch (center) flanked by Mike Seeger and Elizabeth Cotten in 1983; below, a brief documentary.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZmNwVzeoYtE]