Celos aun del aire matan: Fiesta cantada (opera in three acts) (Middleton: A-R editions, 2014) is a critical performing edition of the earliest extant Hispanic opera, Celos aun del aire matan by Juan Hidalgo (1614–85). The work is the most extensive surviving example of Hispanic Baroque theatrical music.

Designed for the Spanish royal court’s festivities honoring the marriage of Infanta María Teresa of Spain and King Louis XIV of France, this passionate fiesta cantada in three acts was first produced in Madrid, thanks to the collaboration of Hidalgo and the court dramatist, Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600–81). The opera was designed for performance by a cast of young female actress-singers (the only role requiring a male voice is for a comic tenor) and a continuo group.

This edition, which includes an extensive introduction, an English translation of the Calderón text, and a unique loa from the 1682 Naples production, contributes to a better understanding of Hidalgo’s music and the contribution of Hispanic music to early modern musical culture.

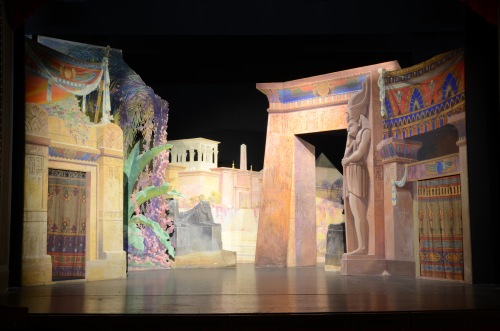

Above and below, moments from a 2000 performance of the work at the Teatro Real in Madrid.