Editor’s note: While this retrospective collection is still available to subscribers, it is no longer offered as a separate product; we have decided to let this post remain online for its historical interest.

EBSCOhost has just launched RILM Retrospective Abstracts of Music Literature.

Reflecting myriad currents of thought—the twilight of Romanticism and the dawn of Modernism, the rise and fall of Marxism, and the advent of multiculturalism, to name just a few—RILM Retrospective offers a fascinating window on intellectual history through the prism of music. This constantly updated database documents an ever-expanding intellectual universe, not a straight line of progressive development. Looking back across the arc of history, we can begin to see how outlooks were formed, and we can assess the roles of the various currents and sidetracks that have shaped the disciplines that we pursue. The unique place of music in human life is salient at every turn.

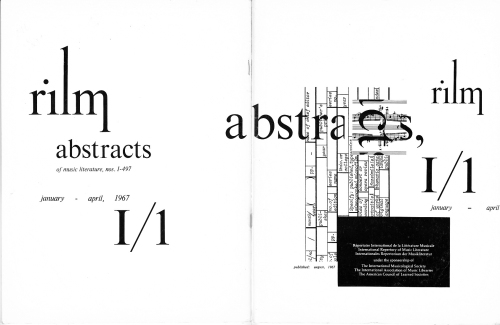

When Barry S. Brook founded RILM in 1966 he set the cutoff date for coverage at 1967; however, he recognized the importance of similar coverage of earlier materials. He therefore initiated a retrospective series and commenced work on a volume that would cover conference reports published before 1967; this book was finally published by RILM in 2004 thanks to a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and its contents, and updates to it, are part of RILM Restrospective. Another project that Brook envisioned, a volume covering Festschriften, was partially completed with a book published by RILM in 2009 thanks to a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities; that book’s contents, along with over twice as many additional records, are also part of this database. RILM is now focusing on retrospective coverage of scholarly journals, adding at least 350 records each month.

Conference reports

Papers presented at conferences represent the cutting-edge research of their day, giving a snapshot of that moment in the development of their fields. Further, the changing nature and frequency of conferences over time can be tracked through this database; for example, The only 19th-century conferences devoted solely to music focused on Gregorian chant, and were held under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church; otherwise, musical topics arose only in conferences devoted to history, folklore, psychology, or questions of public and private property. The first conferences devoted to studies in musicology were held in 1900, in Paris.

Festschriften

Festschriften enact visions of order in both synchronic and diachronic domains. In the synchronic realm, they depict order within, and among, disciplines and institutions. They represent diachronic order in their images of history—also within disciplines and institutions, as well as within the overarching history of music. For example, by 1966 postmodern irony had not yet become fashionable, nor had the new-music world splintered completely. The narrative of contemporary music still related it directly to a salutary evolution from antiquity to the present. Some of the rhetoric of the serialists was downright utopian, and, especially after they had Stravinsky on board, many people assumed that they indeed represented the wave of the future. The academy was also more unified, and while ethnomusicologists were not universally welcomed into music departments, the cutthroat culture wars were yet to be fought.

Journals

Journals, particularly those devoted to specific disciplines or subdisciplines, allow similar tracking of intellectual developments, including the differentiation of particular scholarly streams. For example, before World War II papers on non-Western and traditional Western musics largely came from the field of folklore—a rather woolly domain at that time, whose denizens ranged from wide-eyed dilettantes to rigorous collectors and cataloguers—or from the young sciences of ethnology, anthropology, and psychology. In the 1950s attempts to synthesize the particular challenges and insights involved with all of these studies began to coalesce under the term ethno-musicology (the hyphen was soon abandoned), and beginning around that time several of the scholars involved were using journal articles to try to define their field and its dynamics.

Above, the back and front covers of RILM’s first publication (click to enlarge).