Scholars have long known that Wagner had a deep and lasting interest in Buddhism; less known are the specific insights garnered from Buddhism that are manifested in Parsifal. The key to understanding this connection is the enigmatic figure of Kundry.

Contrary to the common interpretation of Kundry as the incarnation of the will, and in light of Wagner’s admiration for Schopenhauer, she may be seen as the personification of desire. Desiring, which is different from wanting, is a fundamental aspect of Buddhism. As Buddha explained in his very first sermon, desire is the cause of suffering (dukkha). Buddhist teaching holds that suffering can only be overcome when desire is vanquished.

Kundry appears in three forms in Parsifal; these correspond to the three forms of desire in Buddhism. This interpretation aligns the work’s Christian, pagan, and Buddhist symbolism as an expression of the inner way that is shared by all who tread the path of religious mysticism. Through extensive study of Buddhism, Wagner came to understand the deeper side of all religions, a universal truth that all mediators of religious traditions come to understand.

This according to “Kundry: The personification of the role of desire in the holy life” by Pandit Bhikkhu (Cittasamvaro) (Wagnerspectrum III/2 [2007] pp. 97–114; RILM Abstracts of Music Literature 2007-20593).

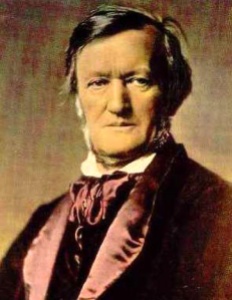

Today is Wagner’s 210th birthday! Above, Christa Ludwig as Kundry; below, Waltraud Meier in the role.