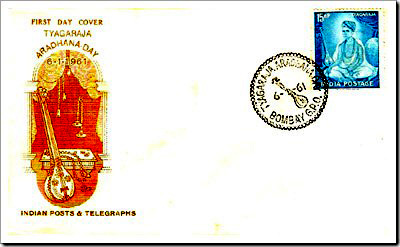

The music philatelist S. Sankaranarayanan has produced monthly articles for the magazine Sruti almost without a break since April 2004.

Each article covers the issuance of a stamp (or group of stamps) by the Indian Department of Posts and includes a philatelic report along with a first day cover and background information on the stamp’s subject—these have included exponents of the Karnatak and Hindustani traditions as well as Indian folk musicians, dancers, musicologists, and patrons of the arts.

Above, a first day cover of a 1961 stamp honoring the Karnatak composer Tyāgarāja (1767–1847); Sankaranarayanan’s article about this stamp appeared in Sruti 269 (February 2007), pp. 40–41.

Related articles: