Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji completed his Second Organ Symphony in 1932. Over 78 years later, on 6 June 2010, Kevin Bowyer premiered the work in a nine-hour marathon; the symphony is longer than Mahler’s first seven combined.

Bowyer performed from his own hand-written edition of the work’s 350+ page score. When he learned of the project, the composer asked a friend “Why is this young man going to such trouble?”

“Well”, the friend ventured, “had your manuscript been much clearer, he might not have had to.” Sorabji promptly retorted that if all his manuscripts had been written with such fastidious care he probably never would have gotten around to writing that symphony at all!

This according to “Sorabji’s second organ symphony played at last: Kevin Bowyer’s nine-hour marathon” by Alistair Hinton (The organ LXXXIX/353 [summer 2010] pp. 41–47).

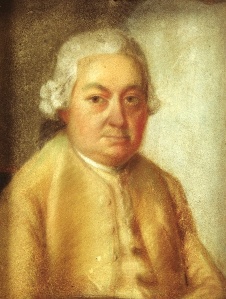

Above, Sorabji in 1933, a year after completing the symphony; below, a much briefer example of his work.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HDY6Dvegu8]

Related article: Sorabji resource site