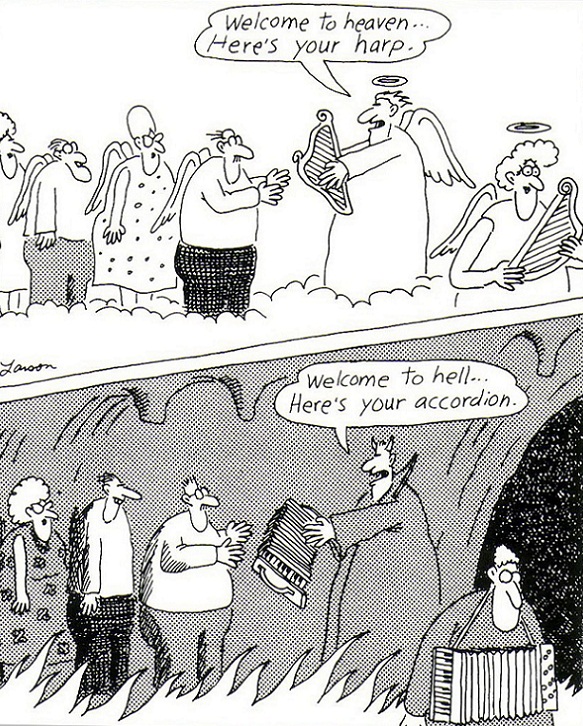

Jokes about accordions often involve their destruction. (The difference between an accordion and an onion: People shed tears when they chop up an onion.) Presumably this is due to their sound. (The difference between an accordion and a macaw: One makes, loud, obnoxious squawks; the other is a bird.)

Indeed, the very presence of the instrument is counted as a misfortune. (A man had to park on the street, and he left his accordion on the back seat. When he returned, he was shocked to see that one of the car’s back windows was smashed, and there were now two accordions on the back seat.)

But the sound of the accordion is identical to that of the reed organ once found in genteel parlors; the instrument’s true fault is its lower-class associations, often involving marginalized ethnic groups and non-mainstream music.

This according to “Accordion jokes: A folklorist’s view” by Richard March, an essay included in The accordion in the Americas: Klezmer, polka, tango, zydeco, and more! (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012 pp. 39–43).

Above, the view from The far side; below, “Werid Al” Yankovic discusses the misfortunes of accordion ownership.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYt6ZwmgbOY]

Related article: Viola jokes