Among the various musical instruments depicted in early documents (bells and double bells, drums, scrapers, horns, flutes, xylophones, and bow-lute), the double bell is of particular interest because of its relatively good pictorial documentation.

In 1687 a double bell from the Congo-Angola area called longa was first mentioned in print. Even today the Ovimbundu people call the double bell alunga (sing. elunga), and give it an important role in the enthronement of the king.

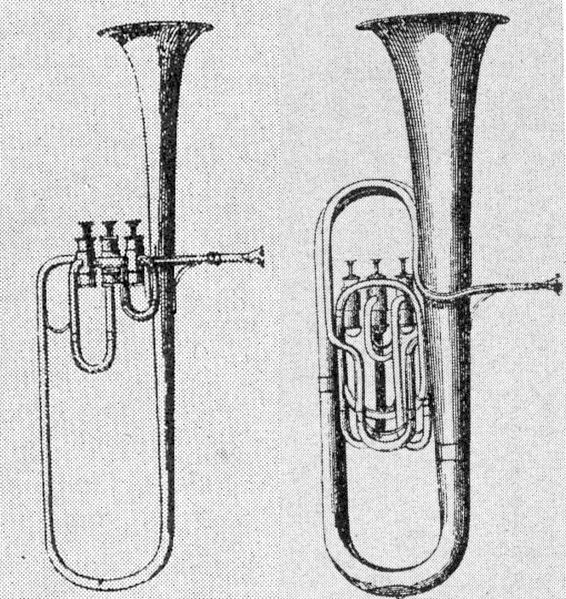

Early pictorial sources and later reports indicate four types of double bell—those with stem grip, bow grip, frame grip, and lateral bar grip—and of these the stem grip double bell, found in the Congo-Angola areas as well as Rhodesia, represents the older type of double bell and probably has its origin in Benin-Yoruba. It appears that the Portuguese, who got to know the double bell as an important court instrument in the Guinea area, brought this instrument, together with other court appurtenances, to Luanda, their new base of operations after the breakdown of the Congo kingdom.

This according to “Early historical illustrations of West and Central African music” by Walter Hirschberg (African music IV/3 [1969] pp. 6–18).

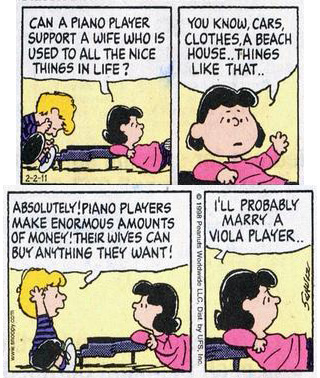

Above, Le triumphe de la noblissement des Gentilhommes, published by Pieter de Marees in 1605. Below, Nigerian double bells and other instruments.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RVwJTXz7j98]