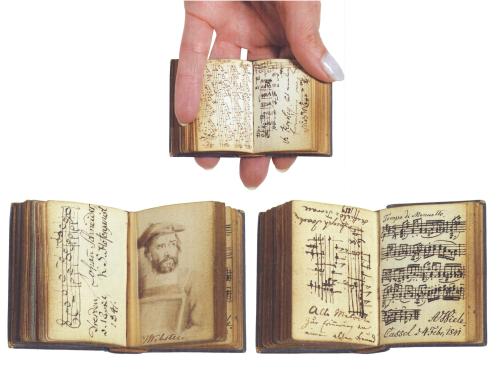

In 1833 Sophy Horsley, a well-heeled British teenager, wrote to her aunt “Mendelssohn took my album with him the night of our glee-party, but you have no idea how many names he has got me.” Over the following years Horsley and Mendelssohn Bartholdy, who was a family friend, collected musical works, illustrations, and autographs in a 144-page album measuring 1⅞ by 1¼ inches.

Composers who contributed works or snippets included Mendelssohn Bartholdy himself along with Bellini, Brahms, Chopin, Liszt, Paganini, and Clara Schumann. Drawings and paintings were contributed by Edwin Landseer, Franz Xaver Winterhalter, and Julius Hübner; inscriptions include contributions by Charles Dickens, Jacob Grimm, and Jenny Lind.

This according to “Sophy’s album” by Anne C. Bromer and Julian I. Edison, an article included in Miniature books: 4,000 years of tiny treasures (New York: Abrams, 2007); the book was published in conjunction with an exhibition at The Grolier Club, New York City, from 15 May through 28 July 2007. Many thanks to James Melo for bringing it to our attention!

Below, Rahmaninov plays his transcription of Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s “Scherzo” from his incidental music for A midsummer night’s dream, written when the composer was a teenager himself.

Related articles: