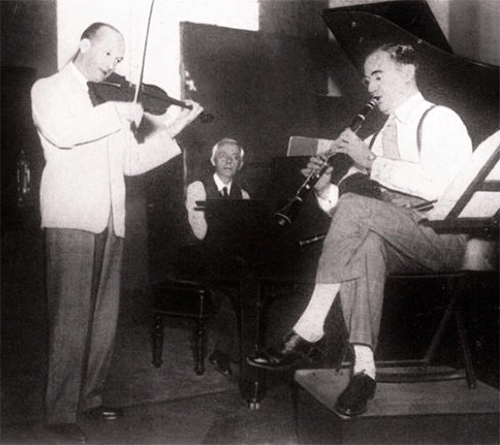

Alfred Hitchcock held an ambivalent position toward the sound elements of cinema. He remained faithful to the idea of pure cinema realized through shots and sequences, and considered dialogue as a lesser expressive resource due to its tendency to break down the narrative tension gained by the images.

On the other hand, he considered sound effects and music to be highly effective devices, with their ability to modify the rhythm of the action, or to voice the depth of characters and the hidden forces of dramatic situations. He often gave sound effects and music central roles in dramaturgy and structure.

The 1956 version of The man who knew too much is a film completely pervaded by music. The recurring song Que sera, sera is one of Hitchcock’s most remarkable examples of diegetic music, informing the audiovisual structures in concurrence with concepts developed by Gilles Deleuze in L’image-mouvement.

This according to “Immagine, suono, relazione mentale in The man who knew too much (1956) di Alfred Hitchcock” by Matteo Giuggioli (Philomusica on-line XI [2007]).

Tomorrow is Hitchcock’s 120th birthday! Above and below, Doris Day’s iconic performance in The man who knew too much.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_91hU6LDjoA]

0

0