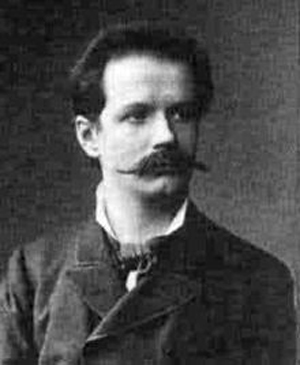

For 20 years Edward Elgar worked for The Gramophone Company as both an advocate of his music and an advocate of the gramophone.

During this period, recording technology changed from the cramped conditions of the acoustic studio of 1914 (above) to the specialized recording studio of Abbey Road using the electrical system of 1933, in which year Elgar conducted his last recordings, with the extraordinary appendix of Elgar supervising a recording by telephone connection from his deathbed in 1934.

As an interpreter of his own music—we cannot comment from direct experience on his success with the music of others, for nothing was recorded—he was as fine a conductor as Furtwängler for Wagner and Mengelberg for Brahms. His conducting ability extended to every aspect of the art, from the purely technical quality of the playing he repeatedly drew from orchestras to the inexhaustible fascination of the interpretations themselves.

This according to “Elgar’s recordings” by Simon Trezise (Nineteenth-century music review V/1 [2008] pp. 111–31).

Today is Elgar’s 160th birthday! Below, Elgar conducts the prelude to The dream of Gerontius in 1927, a recording singled out for praise in the article.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlbLbCn6i3o]

BONUS: Elgar conducts the trio of Pomp and circumstance march no. 1 at the opening of the Abbey Road Studios on 12 November 1931. After mounting the podium, he says to the orchestra “Good morning, gentlemen. Glad to see you all. Very light programme this morning. Please play this tune as though you’ve never heard it before.”

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrzApHZUUF0]