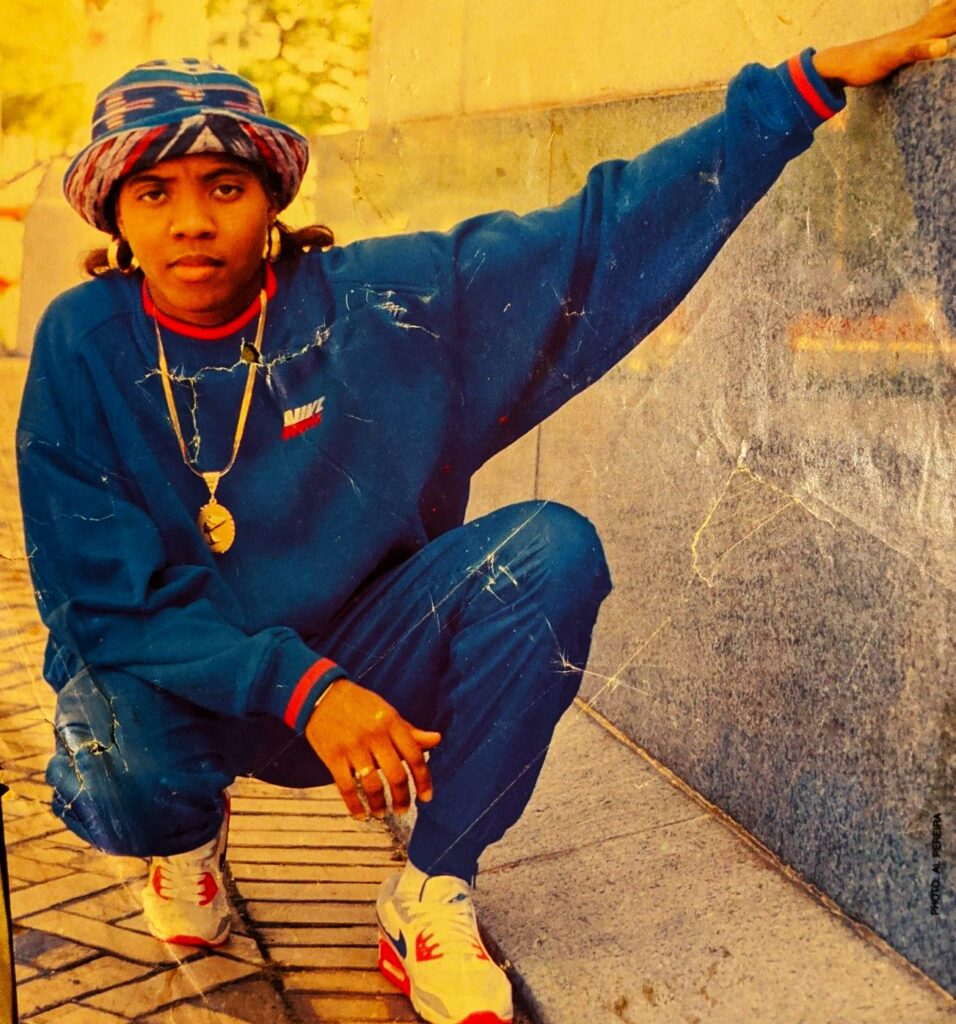

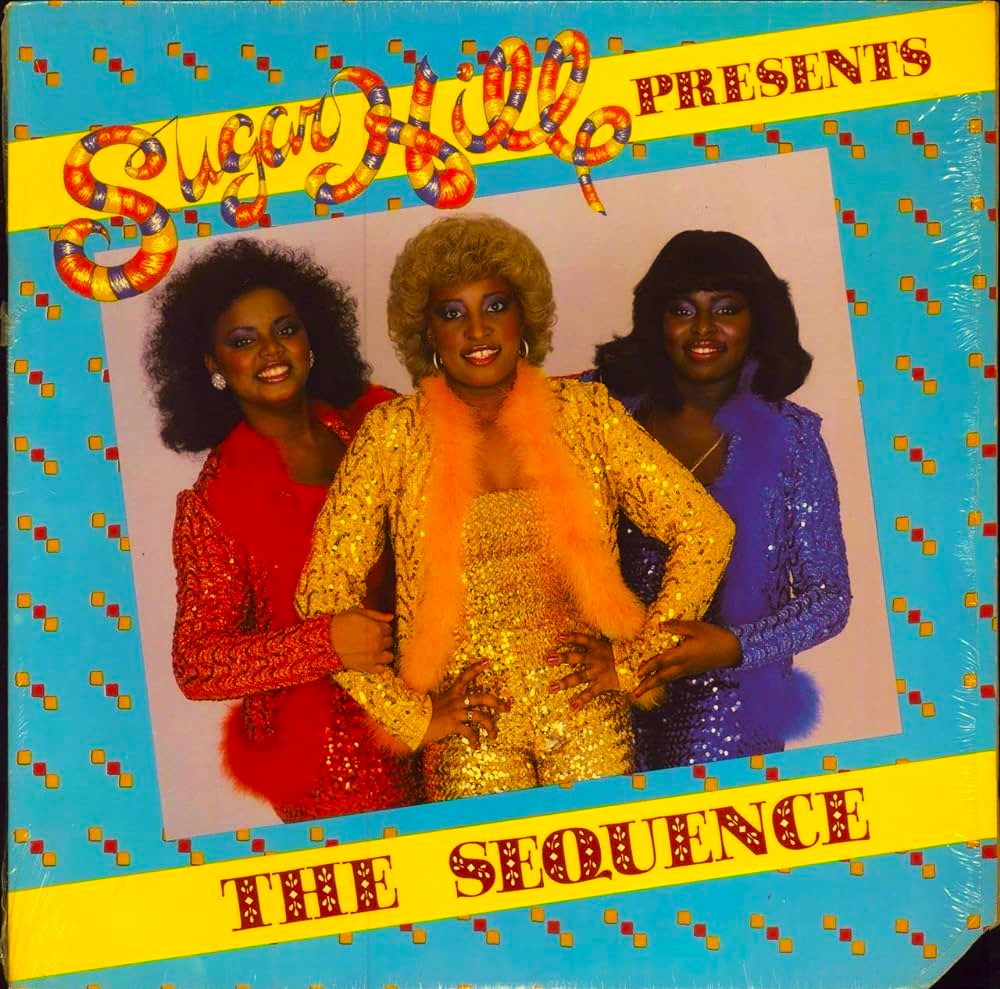

Women have been part of hip hop expression from its early days, primarily as part of MC crews such as the Funky Four Plus One and Sugar Hill’s female group, Sequence. For most of hip hop’s recorded history, however, women MCs were mostly seen as novelty acts, with a few exceptions. In the mid-1980s, some female artists were popularized momentarily through answer

songs, which ridiculed popular songs by male acts. These answer songs included Roxanne Shante’s Roxanne’s revenge (responding to UTFO’s 1984 song Roxanne, Roxanne) and Pebblee Poo’s Fly guy (responding to the Boogie Boys’ 1985 song A fly girl).

Some of the most enduring female hip hop acts released premiere albums in 1986. Salt-N-Pepa was the most commercially successful hip hop group with its first album, Hot, cool and vicious. Queen Latifah emphasized strong social messages and women’s empowerment on her first album, All hail the queen. MC Lyte recorded her first album, Lyte as a feather, at this time. Many women artists who appeared or recorded during the early 1990s adopted the extant masculine-oriented hip hop images prevalent in hardcore rap music. MC Lyte, for example, recorded a hardcore album in 1993 entitled Ain’t no other–the album’s first hit single, Ruffneck, was MC Lyte’s first gold-selling single. After the decline of gangsta rap music in the mid- to late 1990s, women remained on the periphery of mainstream hip hop, apart from the occasional pop hit, such as the platinum-selling Atlanta-based artist Da Brat’s Funkdafied (1994).

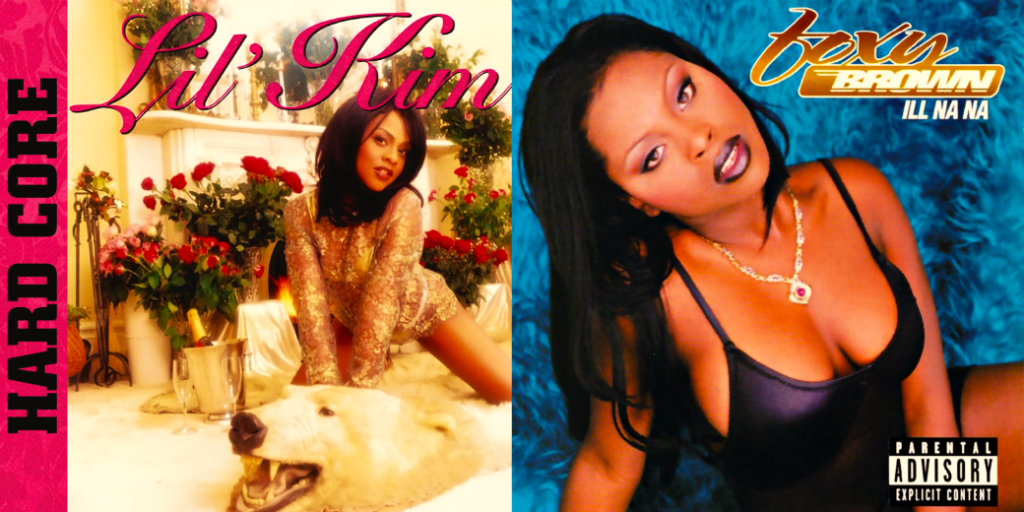

By the late 1990s, artists such as Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown publicly celebrated or exploited female sexuality through explicit lyrics and widespread publicity campaigns that presented these scantily clad artists as sex symbols. For the most part, however, women artists failed to receive respect within the hip hop community as competent MCs and recording artists, although achieving mainstream success. Many of the writers and producers for the female groups were men, particularly through the late 1990s. The year 1998, however, was pivotal for women in hip hop, especially as rapper-producer-songwriter Missy Elliot began gaining notoriety with her debut album, Supa dupa fly (1997).

Learn more in The Garland encyclopedia of world music. The United States and Canada (2013). Find it in RILM Music Encyclopedias.

Below are some videos from this early period of hip featuring women rappers. First up is the music video for Queen Latifah’s Ladies first, followed by Roxanne Shante performing Roxanne’s revenge (on VHS tape from around 1984!), and a 1985 recording of Pebblee Poo’s Fly guy.