Die Lebensfreude is a pioneering piece of music composed with the aid of an amoeba-like plasmodial slime mold called physarum polycephalum.

The composition is for an ensemble of five instruments (flute, clarinet, violin, cello and piano) and six channels of electronically synthesized sounds. The instrumental parts and the synthesized sounds are musifications and sonifications, respectively, of a multi-agent based simulation of physarum foraging for food.

Physarum polycephalum inhabits cool, moist, shaded areas over decaying plant matter, and it eats nutrients such as oat flakes, bacteria, and dead organic matter. It is a biological computing substrate, and has been enjoying much popularity within the unconventional computing research community for its astonishing computational properties.

This according to “Harnessing the intelligence of physarum polycephalum for unconventional computing-aided musical composition”by Eduardo R. Miranda, an article included in Music and unconventional computing (London: AISB, 2013).

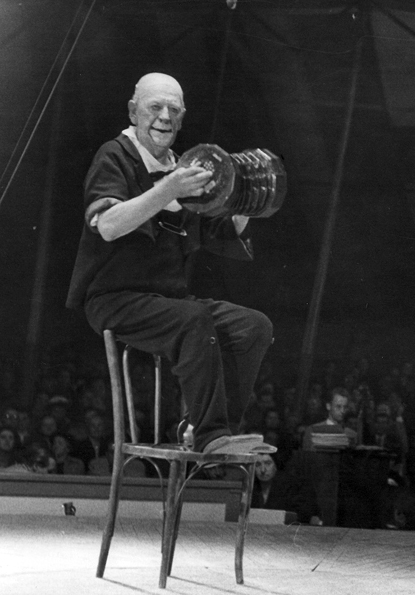

Many thanks to the Annals of Improbable Research for bringing this to our attention! Above, the co-composer; below, the work’s premiere.