In canonical French Orientalist discourse of the 19th century, the Orient is cast as effeminate, weak, and in need of rehabilitation by Western civilization. However, the dramatic arts of late 16th- and early 17th-century France constructed a different picture, one in which the Orient as temptress was a deadly threat to the West.

During the late Valois and early Bourbon monarchies, the queen regents Catherine de Médicis (1519–89), Marie de Médicis (1575–1642), and Anne d’Autriche (1601–66) were associated with political turmoil and civil war that threatened to destroy the kingdom. Within this troubled political context, fatal women of the Orient sought to entice their prey on the French stage. Most deadly among them was Cleopatra, embodiment of Egypt, incarnation of women’s malignant sexual seduction, exposed in her subjugation of Marcus Antonius, the fallen, conquered, and emasculated Roman.

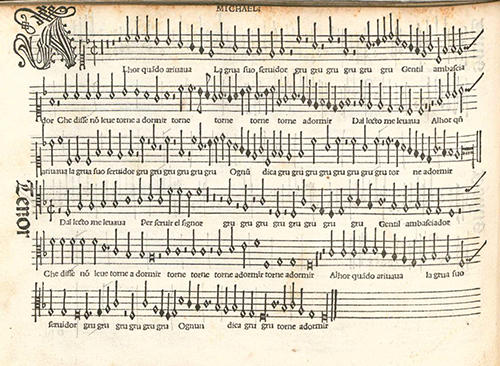

With the rise of Louis XIV (1638–1715) and his imposition of a purportedly indomitable and masculine monarchy, women were to be vanquished outright. Reigning women, including those in the tragedies of Philippe Quinault (1635–88), were the victims of self-destructive passions ending in defeat, death, or abandonment by the heroes whom they sought to enslave. An emblematic example of such a crushed woman is the sorceress Armide in the tragédie en musique by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–87), the libretto of which is by Quinault.

This according to “Regnorum ruina: Cleopatra and the Oriental menace in early French tragedy” by Desmond Hosford, an essay included in French Orientalism: Culture, politics, and the imagined Other (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010, 23–47; RILM Abstracts of Music Literature 2010-6408).

Above, a 17th-century depiction of Cleopatra by Claude Vignon; below, Stéphanie d’Oustrac portrays Armide’s downfall.