The Strong Women from the Tiwi Islands (northern Australia) are concerned that young Tiwi people are straddling two cultures, losing their language and their Tiwi identity.

To address this problem, the women and their grandchildren have composed a song that emphasizes connection to the ancestors, to country, to language, and to the elders. With lyrics in English, traditional Tiwi song language, and the contemporary spoken language, and with a hip-hop dance-mix sampling an ethnographic recording made in 1912, Ngariwanajirri (Strong kids song) is an example of new music helping to preserve tradition.

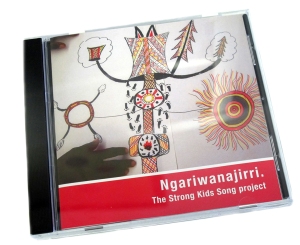

This according to “Ngariwanajirri, the Tiwi Strong kids song: Using repatriated song recordings in a contemporary music project” by Genevieve Campbell (Yearbook for traditional music XLIV [2012] 1–23).

Below, a music video of Ngariwanajirri; the song changes dramatically around 2:00.