In the laboratories of 19th-century experimental psychologists, new concepts of precision-oriented, mechanically regulated musical time emerged as a positive ideal—one that led to the ubiquity of the metronome in the training and practice regimes of classical musicians and pervasive understandings of “good” and “bad” musical rhythm in the 20th century.

Most notably, Wilhelm Wundt included a metronome in the assembly of clockwork instruments employed in his research into the variables of human perception and action. His experiments helped to shape and define modern concepts of rhythm, radically shifting the concept of musical rhythm from a subjective, internal pulse reference to an objective, unerringly precise phenomenon independent of human agency.

At the turn of the 20th century, other psychologists, such as Carl Seashore, disseminated these scientific ideals to a wider public through important music publications, and by the 1920s such ideals were becoming pervasive among both amateur and professional music practitioners.

This according to “Refashioning rhythm: Hearing, acting and reacting to metronomic sound in experimental psychology and beyond, c. 1875–1920” by Alexander Bonus, an essay included in Cultural histories of noise, sound and listening in Europe, 1300–1918 (Abington: Routledge, 2017, pp. 76–105).

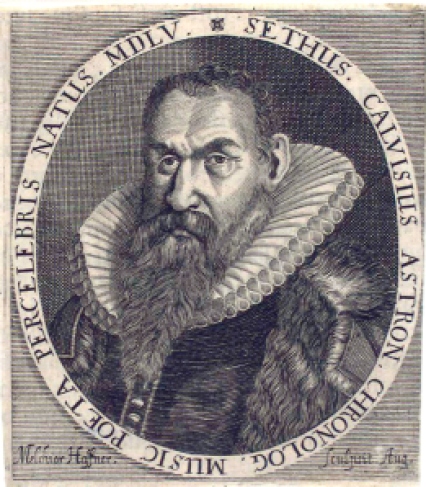

Above, Dr. Wundt (seated) and colleagues in his psychological laboratory, the first of its kind, ca. 1880; below, an abridged version of György Ligeti’s Poème symphonique for 100 metronomes.

BONUS: For the purists, a complete performance of Ligeti’s work.