Jenny Lind Concert Program, 1850, National Museum of American History, Gift of Sarah Ella Cummings.

“Music is prophesy. Its styles and economic organization are ahead of the rest of society because it explores, much faster than material reality can, the entire range of possibilities in a given code. It makes audible the new world that will gradually become visible. It is not only the image of things, but the transcending of the everyday, the herald of the future.” –Jaques Attali

Jenny Lind, aka the “Swedish Nightingale,” was a nineteenth-century European opera singer who helped birth American popular music and celebrity culture as we know it today. By the estimation of historian Neil Harris writing in his book Humbug: The Art of P.T. Barnum, following the massive success of her 1850–52 tour of American concert halls (including Musical Fund Hall in Philadelphia), “Jenny Lind had become and would remain the greatest musical sensation of the nineteenth century.” How and why did this happen, and what did it mean for the future of popular music and celebrity culture? In his chapter on Lind, whose U.S. concert tour was proposed and publicized by Barnum—an equal partner in the tour’s profits of course—there are several salient factors.

For one, Lind was promoted not only as a marvelously talented artist, but also as an avatar of nature itself, as suggested by the “Swedish Nightingale” sobriquet that was first bestowed by the English. Praised by American audiences as much for her plain clothes, modest deportment, and charity work as for her voice, Jenny Lind’s natural authenticity was as crucial to her popularity as was the labor-intensive effort and artifice more commonly associated with the operatic voice.

Under P.T. Barnum’s supervision, “biographies were prepared and distributed” months before Lind arrived in the States, “emphasizing Jenny’s piety, her character, her interest in philanthropy and good works.” The enthusiasm that Barnum managed to whip up for Lind’s tour led to a phenomenon then known as “Lindomania.” On her arrival to the New World, the New York Herald reported “the spectacle of some thirty or forty thousand persons congregated on all the adjacent piers,” people described as being “from all quarters [and] crowds.” Compared with the advent of Beatlemania and their similarly-hyped arrival in New York, Lind attracted crowds ten times as big as the Fab Four.

A final crucial point in this publicity campaign, returning again to the Harris text, is that “all of this extraordinary enthusiasm” was “designed to reflect credit not only on the object of veneration but the venerators themselves.” Landing in an America that had yet to develop well-known artistic and expressive forms distinctly its own, the nation suffered somewhat of an inferiority complex, especially when faced with venerated art and artists from the Continent. As Harris points out, “The spectacle of a proud republic voluntarily paying homage to a young woman (Jenny was already thirty but invariably described by Americans as a young girl) of great artistry demonstrated that the finer values, which Europeans had insisted were swamped by money-getting and chicanery, still ruled the New World.” Crucially, Barnum and Lind would flip the script here, the tour serving as a turning point in American culture where art and talent, money and chicanery, would be fused into a distinctly American art world later labeled as “popular culture” and “popular music,” and where fame was transformed into celebrity.

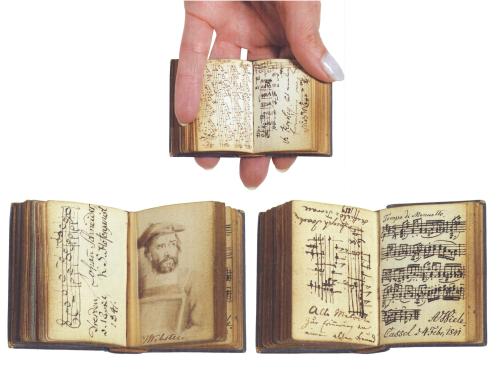

Fame is often contrasted to celebrity as a matter of talent and accomplishment (fame), versus mere notoriety for whatever reason or through whatever means (celebrity). But above and beyond this distinction—and bearing in mind that even so-called “meritocracies” are riven with subjective distinctions and prone to the biases of the already-powerful classes—celebrity is all about celebration. And this celebration extends far beyond the object of veneration (Jenny Lind in this case), but also to those doing the celebrating, who see their own ideals, tastes, and morals either reflected in a famous figure, or perhaps (in many of celebrity’s more recent manifestations) celebrate themselves as superior to the “pathetic” celebrities who will do anything to be famous. And finally, celebrity celebrates its own mechanisms and operational aesthetics. In a celebrity culture, credit is openly bestowed upon the publicists and other promoters (including celebrities themselves when serving in this capacity) and to the wider entertainment industry and advertising industry that perpetuate celebrity culture. Prescient evidence of this perspective is seen in the concert program pictured here—where advertisements for daguerreotype artists, portraitists, hairdressers, and tailors (nineteenth-century image-making enterprises one and all) were placed alongside the musical program itself, implicitly celebrating the image making behind Lind’s own celebrity.

To be sure, Lind came by her fame honestly. While no recordings of her exist, by all reports her singing was impressive enough that many listeners described it in transcendent terms. But she was also one of the first celebrities in the modern sense of the word—famous not only due to observable talent and accomplishment, but celebrated also for her sheer visibility, celebrated as a highly-promoted persona, one who was considered highly relatable to her public, a Platonic ideal of socially-desirable traits as perceived by her audience (notably, in more recent decades, it’s just as often the case that these “Platonic ideals” are the undesirable traits of a given anti-hero celebrity whose métier is controversy and outrage). For Jenny Lind, the constructed nature of her celebrity is highlighted by the fact that most of her “fans” had never heard her sing before, including P.T. Barnum himself as he undertook his publicity blitz before her arrival. By his own account, Barnum effectively “transformed the admittedly already famous ‘Swedish Nightingale’ into a celebrity, accompanied by endorsements, spin-off products, and fabulously successful concerts in many American cities” (Barnum).

Most readers today are familiar with P.T. Barnum as the famed American figure who turned carnival barking into a mass-mediated, wildly lucrative art form of its own—in many ways laying the foundation for the American entertainment industry and the advertising industry. Widely perceived as a hustler and a flim-flam man, or as an ahead-of-his-time impresario and the ultimate self-made man (see Hugh Jackman’s portrayal in 2017’s sleeper hit film The Greatest Showman, dir. Michael Gracey), the truth likely lies somewhere in between. Barnum was a man who created mass entertainments that combined pure spectacle, earnest pedagogy-for-the-people, and shameless chicanery (often at the people’s literal expense) at legendary institutions like Barnum’s American Museum and Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth (later, the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus). His promotion of Jenny Lind, well after his public image was cemented in place, was Barnum’s (largely successful) attempt to go legit—a famed hoaxer and huckster applying his promotional acumen to the highest of high culture.

As it turns out, the carnivalesque “low culture” that Barnum trafficked in was more than compatible with the elite culture of opera. Thanks in large part to Barnum’s promotional efforts in the months leading up to her arrival, once Lind reached American shores the operatic wunderkind was already “venerated like a saint…because of her modest character and her charitable activities” (Bruckmüller–Schindler) as much as for her singing. Despite the highbrow, elite affiliations associated with opera in the nineteenth century, especially among Americans who were far removed from European cultural centers, Barnum ingeniously aimed his advertising at those very “non-elite” outsiders with Lind portrayed as an outsider in her own right—a public image “constructed from her humble origins, demonstrations of concern for the underprivileged, her rejection of the opera stage and its elite audience, and her embodiment of the American ideal of womanhood” (Caswell). When it comes to the latter, her image was framed as “[running] counter to cultural associations of prima donnas with women of dubious lifestyles and questionable character” (Biddlecombe). In other words, she was a prima donna suitable for the established gender norms and the lingering Puritan morals, whether in practice or merely in principle, of the American audience.

While Jenny Lind’s largely-unheralded role in American popular music history may seem a bit contradictory—a European who helped birth a distinctly American culture, an opera singer who was one of the first icons of modern popular culture—it only reinforces how such contradictions lie at the heart of any definition of “the popular” as widely understood in contemporary culture. Popular music, in particular, is defined equally by its bottom-up populist nature (the music of the people) and its top-down commercial basis (filtered through the machinations of the music industry). What’s more, given the perceived inauthenticity of “popular culture”—even among many of those who most enthusiastically participate in the popular culture and consume its products—an offsetting “authenticity discourse” is central to much of popular music culture in which musical celebrities are constantly at pains to establish and maintain their perceived authenticity.

As laid out by Barker and Taylor (see bibliography below), far from being a simple metric, authenticity can be divided between various subcategories such as “representational authenticity” (the talents and abilities of a musician on display minus any behind-the-scene deception or technological enhancement), “cultural authenticity” (Does the musical expression arise “naturally” from a given subculture or other rank-and-file social grouping?), and personal authenticity (Does the music speak to and about the performer’s real life and identity?). These parameters are all the more potent in measuring the authenticity of singers, whether amateur or professional, given that, “voice has a long history in modern Western culture as a transparent signifier of subjectivity and presence” (Vella), and Jenny Lind was perceived as the gold standard of all three categories in her day.

This is all closely linked to what Neil Harris refers to as an “operational aesthetic” in which the hidden story behind a given person, object, or activity—and it’s factual recounting—is just as important as the person, object, or activity itself. In the world of celebrity, the “hidden” star narratives, especially when recounted in breathless Behind the Music style, are just as central to popular music stars’ reception as the music itself. This aesthetic is likely attributable to a range of factors as laid out by Harris in his critical/cultural biography of P.T. Barnum, ranging from American individualism and do-it-yourself aspirational ideas (“the self-created man”) to the rapid rate of advancement in technology (making the seemingly impossible possible) and advertising (the science of convincing others through whatever means). Harris sums up the operational aesthetic thusly: “an approach to reality and to pleasure [that] focused attention on their own structures and operations…an approach to experience that equated beauty with information and technique, accepting guile because it was more complicated then candor.”

Entire sectors of the entertainment industry are now based around “behind the scenes” forensic examination of plainly false realities (e.g., reality television). Reality show producers and music documentarians understand exactly what Barnum came to understand over a century and a half ago: “that the opportunity to debate the issue of falsity, to discover how deception has been practiced, was even more exciting than the discovery of fraud itself…[where] people paid to see frauds, thinking they were true, [and] paid again to hear how the frauds were committed.” Perhaps, echoing into the new millennium, this operational aesthetic still resonates in part, given the routine unrealities of our own lives and the constant self-aware exertion that lies behind our own self-authoring. Whether trolling for “likes” on Facebook, or tweeting at and about celebrities on another social media platform, most of us today inhabit a celebrity-like ecosystem, authoring our own personal star-texts minus the actual stardom. In this and other respects, Jenny Lind anticipated the current age of social media and its promise of celebrity-for-all.

This post was produced through a partnership between Smithsonian Year of Music and RILM with its blog Bibliolore.

Written and compiled by Jason Lee Oakes, Editor, Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale (RILM).

Bibliography

Barker, Hugh and Yuval Taylor. Faking it: The quest for authenticity in popular music (New York: W.W. Norton, 2007). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2007-4996]

Whether it be the folklorist’s search for forgotten bluesmen, the rock critic’s elevation of raw power over sophistication, or the importance of bullet wounds to the careers of hip-hop artists, the aesthetic of the “authentic musical experience”, with its rejection of music that is labeled contrived, pretentious, artificial, or overly commercial, has played a major role in forming musical tastes and canons, with wide-ranging consequences. The question of authenticity in popular music is not only fundamental to understanding the music’s history, but fundamental to thinking about, listening to, and performing it as well. This question is tackled by examining turning points in popular music’s authenticity in relation to the blues, segregation in the Southern U.S., Alan Lomax’s field recordings, blackface minstrelsy, the birth of modern country music, Elvis Presley’s reinvention of rock ‘n’ roll, bubblegum pop in the era of singer-songwriters, the Monkees’ decision to play their instruments, Donna Summer’s 17-minute faked orgasm as the defining moment of disco, the “public image” of the Sex Pistols and punk rock, Kurt Cobain’s choice of a Leadbelly song as his swan song on MTV’s Unplugged, and Moby’s use of Alan Lomax’s field recordings in a sample-based electronic-music setting. The careers of John Lennon, Jimmie Rodgers, John Hurt, Neil Young, and the KLF are examined through the lens of authenticity. (Jason Lee Oakes)

Barnum, Phineas Taylor (P.T.). “P.T. Barnum and the Jenny Lind fever”, Music in the USA: A documentary companion, ed. by Judith Tick and Paul E. Beaudoin. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008) 185–189. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2008-36741]

The American promotion of the great soprano Jenny Lind by P.T. Barnum represents a watershed in the music business. Barnum transformed the admittedly already famous “Swedish Nightingale” into a celebrity, accompanied by endorsements, spin-off products, and fabulously successful concerts in many American cities. A risk taker, as shown in this selection from his Struggles and triumphs, or, Forty years’ recollections of P.T. Barnum (Hartford, J.B. Burr, 1869), Barnum offered Lind a huge contract for an American tour without hearing her sing. He exercised his genius in marketing and publicity, foreshadowing the extent to which these would become industries unto themselves in the following century. (editors)

Biddlecombe, George. “Jenny Lind, illustration, song and the relationship between prima donna and public”, The idea of art music in a commercial world, 1800–1930, ed. by Christina M. Bashford and Roberta Montemorra Marvin. Music in society and culture (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2016) 86–113. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2016-2056]

Focusing on the role of imagery in promoting an idealized notion of Jenny Lind in Britain and the U.S., this essay explores how constructions of Lind’s persona in sheet music and other material commodities ran counter to cultural associations of prima donnas with women of dubious lifestyles and questionable character. By analyzing images of Lind on the sheet-music covers of ballads that she sang publicly, the author demonstrates that most of the illustrations were based on two paintings of her that signal femininity, innocence, and physical attractiveness. Some of the covers, along with commercially available prints of Lind, also enhanced her body and facial features to create an aura of beauty and unimpeachable morality. Since sheet music was mostly intended for the middle-class domestic sphere and likely purchased, played, and sung by young, often unmarried, women (for whom music-making was an important part of courtship), the Lind products were targeted at this group, in the hope of encouraging consumers to identify with the soprano and even to believe that a famous female singer was endorsing their own domestic space. Moreover, the author explores the qualities that attached to the English-language ballads Lind sang in concerts in both Britain and the U.S., arguing that this repertoire connoted modesty, domesticity, emotional restraint, and even national character and political values. Her performance of the repertoire created an ideology that further revealed the singer’s “internal self” and complemented the idea of Lind that was circulating in printed imagery. (Christina M. Bashford)

Bruckmüller-Schindler, Magdalena. “The diva between admiration and contempt: The cult state of exceptional music artists in the 19th century”, Europe in the time of Franz Liszt, ed. by Valentina Bevc Varl and Oskar Habjanič. (Maribor: Pokrajinski muzej Maribor, 2016) 150–161. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2016-44231]

Discusses aspects of the star cult of female opera singers at the beginning of the 19th century. It starts with a short introduction about stars and virtuosos who were deeply burnt into the collective memory, such as Liszt or Paganini, and then focuses on the “prima donnas”, who during their lifetimes were enormously successful and even venerated as almost godlike. Nowadays, they have been almost forgotten, but during their lifetimes some of them filled newspapers with gossip, leading to astonishment, but also to extreme forms of admiration. The apotheosis of the “diva”, Maria Malibran (1808−36) in the hour of her early death is the first of three episodes that are told in this article. The second is about the “Swedish Nightingale” Jenny Lind (1820−87), who was equally venerated like a saint also because of her modest character and her charitable activities. Adelina Patti, as the third in the group, shows how the word diva was reversed into a negative sense. Diva became synonymous with a scandalous and wasteful lifestyle—and was even used in a chauvinistic way.

Caswell, Austin B. “Jenny Lind’s tour of America: A discourse of gender and class”, Festa musicologica: Essays in honor of George J. Buelow, ed. by Thomas J. Mathiesen and Benito V. Rivera. Festschrift series 14 (Stuyvesant: Pendragon Press, 1995) 319–337. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1995-12612]

Jenny Lind, during her 1850–52 tour of the U.S., attracted a predominantly non-elite audience that took her as their own. This identity was constructed from her humble origins, demonstrations of concern for the underprivileged, her rejection of the opera stage and its elite audience, and her embodiment of the American ideal of womanhood. A tangible service to her credit and class was to temporarily restore to the non-elite the very music that others appropriated as a private preserve. (author)

Gallagher, Lowell. “Jenny Lind and the voice of America”, En travesti: Women, gender subversion, opera, ed. by Corinne E. Blackmer and Patricia Juliana Smith. Between men—between women: Lesbian and gay studies (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995) 190–215. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1995-1209]

The prima donna who enacted the part of the long-suffering female victim must be a chaste goddess able to transcend earthly existence. During her mid–19th-century tour, Jenny Lind’s audience looked to her magical power to heal the social divisions of the nation. Lind made every attempt to fulfill her devotees’ expectations, and the playful perversity of opera’s gender-bent past gave way to a fetishist mode of diva-worship. (Judy Weidow)

Harris, Neil. Humbug: The art of P.T. Barnum (Repr. ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981). [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 1981-24440]

This carefully researched study of America’s greatest showman, huckster, and impresario is both an inclusive analysis of the historical and cultural forces that were the conditions of P. T. Barnum’s success, and, as befits its subject, a richly entertaining presentation of the outrageous man and his exploits. (publisher)

Newman, Nancy. “Gender and the Germanians: ‘Art-loving ladies’ in nineteenth-century concert life”, American orchestras in the nineteenth century, ed. by John Spitzer. (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2012) 289–309. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2012-3608]

Drawing upon the work of Adrienne Fried Block (particularly the article abstracted as RILM Abstracts of Music Literature no. 2008-1343) on the continuum of female activity, from audiences and patrons to teachers and performers, as the mechanism through which U.S. women became incorporated into public musical life in the 19th century. This essay applies Block’s perspective to the situation of the Germania Musical Society. The members solicited women’s interest in multiple ways, offering matinees, engaging accomplished female artists, and publishing sheet music. The picture that emerges is that the Germanians recognized that women were essential to their corporate, commercial, and musical success. They also seem to have found their dealings with the opposite sex personally rewarding. This combination of professional and personal motives offers insights into the U.S. orchestra’s role in the evolving gender relations of modern urban life. Among the featured women performers were Jenny Lind (1820–87), Henrietta Sontag (1806–54), Camilla Urso (1842–1902), and Adelaide Phillipps (1833–82). (author)

Oakes, Jason Lee. “Listen to me now: Social media, celebrity, and popular music”, IASPMUS (2011) http://iaspm-us.net/pop-talk-listen-to-me-now-social-media-celebrity-and-popular-music-part-i-by-jason-oakes/. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2011-4108]

Celebrities dominated much of the public discourse of the 20th century, especially given the endless media coverage of their every triumph and tribulation. In the 21st century, many of these same “triumphs and tribulations” have bled over into the lives of the non-famous, with certain aspects of daily life coming to resemble the rarefied world of celebrities. Consider the rise of surveillance and resulting loss of privacy for the average citizen; the newfound power to broadcast one’s thoughts, actions, and movements to a limitless audience on social media; the addictive pull of self-validation, and the dread of being ignored or anonymously harassed this can produce; and the lack of financial security in a jackpot economy with increasingly long odds at success, but ever-more outsized rewards. Celebrity culture can thus be thought of as an emergent formation, one that is moving toward being a dominant formation, helped along by the rise of social media. Popular music has played a central role in these cultural transformations. When it comes to celebrity, popular music is the realm where fame has been most consistently, deliberately, and insightfully thematized. In many cases, stars and fans of popular music have taken on the role of organic intellectuals, analyzing the “fame game” at the same time they participate in it (the commentary around music-based Internet celebrities such as Rebecca Black, Chris Crocker, Tad Zonday, and Gary Brolsma, aka The Numa Numa Guy, provides one recent example). When it comes to social media, popular music has been at the center of every major development, both in terms of new technologies and in terms of people’s engagement with and understanding of social media. Napster, MySpace, YouTube, and Facebook are examined in this light. Given this track record, and given music’s prophetic power as theorized by Jacques Attali, it is likely that popular music will continue to point the way forward in the rapidly evolving social and technological landscapes of the 21st century.

Samples, Mark C. “The humbug and the nightingale: P.T. Barnum, Jenny Lind, and the branding of a star singer for American reception”, The musical quarterly 99/3–4 (fall–winter 2016) 286–320. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, 2016-40602]

Analyzes P.T. Barnum’s pre-arrival promotional campaign for Jenny Lind’s American tour, and the effects that it had on Lind’s reception in the American press after her first concert in New York on 11 September 1850. This campaign constitutes the crucial process by which Barnum transformed Lind’s reputation in the American mind from a little-known European singer to a household name. The author interprets Barnum’s campaign as an early example of branding, a brand being defined as a dynamic, designed system of signs that mediates the relationship between producers and consumers. To create the “Lind brand”, Barnum orchestrated a campaign unprecedented in cost, scale, duration, and coherence. It established the main reception narratives that followed. From a musical perspective, it is perhaps easy to overlook this promotional campaign as peripheral and therefore subordinate to concerns such as repertoire selection and performance. Yet Barnum’s skilled guidance of the public’s view of Lind was not subordinate but generative, teaching listeners of all classes how to receive Lind, how to experience her artistry, and how to distinguish her from previous star singers who had toured in the United States. Though he would not have called Lind’s publicity campaign “branding”, Barnum bore in mind the tastes of the time as he launched it. He set the context for Lind’s American reception, as well as for the conversations about her in newspapers and other arenas of public discourse. The Lind campaign is notable both for its influence on musical promotions after the Lind tour and as an example of the potential that branding theory has as a methodological tool in cultural musicology. (author)

Vella, Francesca. “Jenny Lind, voice, celebrity”, Music & letters 98/2 (May 2017) 232–254. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature with Full Text, 2017-33082]

Voice has a long history in modern Western culture as a transparent signifier of subjectivity and presence. This ideology of immediacy has meant that exploration of singing voices as mediated has mostly been confined to classic technological turns marked by specific sound devices. This article examines voice in connection with the mid–19th-century soprano Johanna Maria Lind-Goldschmidt, known as Jenny Lind, and the broader London context of contemporary Lind mania. Mediation lends itself to canvassing questions at the crossroads of voice and celebrity studies, for the invocation of a linear, unmediated communication between particular individuals and their audiences lies at the heart of modern celebrity culture’s apparatus. The tension between voice and techne, presence and absence, evinced by printed and visual materials, suggests mediation was key to the perceptual and ideological system surrounding Lind’s voice. Attending to voice within a more porous, relational framework can help us move away from a concern with individuality and authenticity, and listen to a rich tapestry of human and material encounters. (journal)