As a central figure in the 1980’s Chicago noise rock scene with his band Big Black, the famed indie recording engineer/producer Steve Albini developed a reputation for his distinctly anti-commercial work ethic and ability to effectively convey gritty, abrasive noise. Albini’s stance was once described by the scholar and composer Marc Faris as constructing “a gender-, race-, and class-specific workingman persona”. Albini normally wore worker’s overalls (as in the photo above) while in the studio and described his approach to music recording in terms of construction or “putting together”, similar to a bricklayer or steelworker, touting a liveness to his sound by avoiding nonessential studio trickery. As part of the Chicago scene, Albini forged an aesthetic that mixed a musically exact virtuosity with a emphasis on communal music performance.

This aesthetic embraced a documentary approach to studio recording where record production honestly conveyed a band’s live performance with transparency and fidelity. Drums and guitar recording under Albini’s expertise were rendered with startling immediacy and liveness, allowing for the ostensibly natural sound of the performance and performing space to be aurally inscribed in the recording. This aspect of his craft was often described in terms of capturing the essence of a live band. Albini’s recording of vocals, however, often left them buried in the mix. He described his reasoning for focusing on instrumental elements of rock: “In the pop music tradition, the vocal is always the paramount thing . . . In records that are of a band . . . the vocals may not be the most important thing. Now, I can’t count the number of times that a vocalist has said, ʽOkay, it’s time to do the vocals on this. Give me a minute, I have to write some lyrics’”. With such reasoning, Albini placed a modernist aesthetic of instrumental performance squarely against the historically feminized, emotional pop aesthetic of vocal expression.

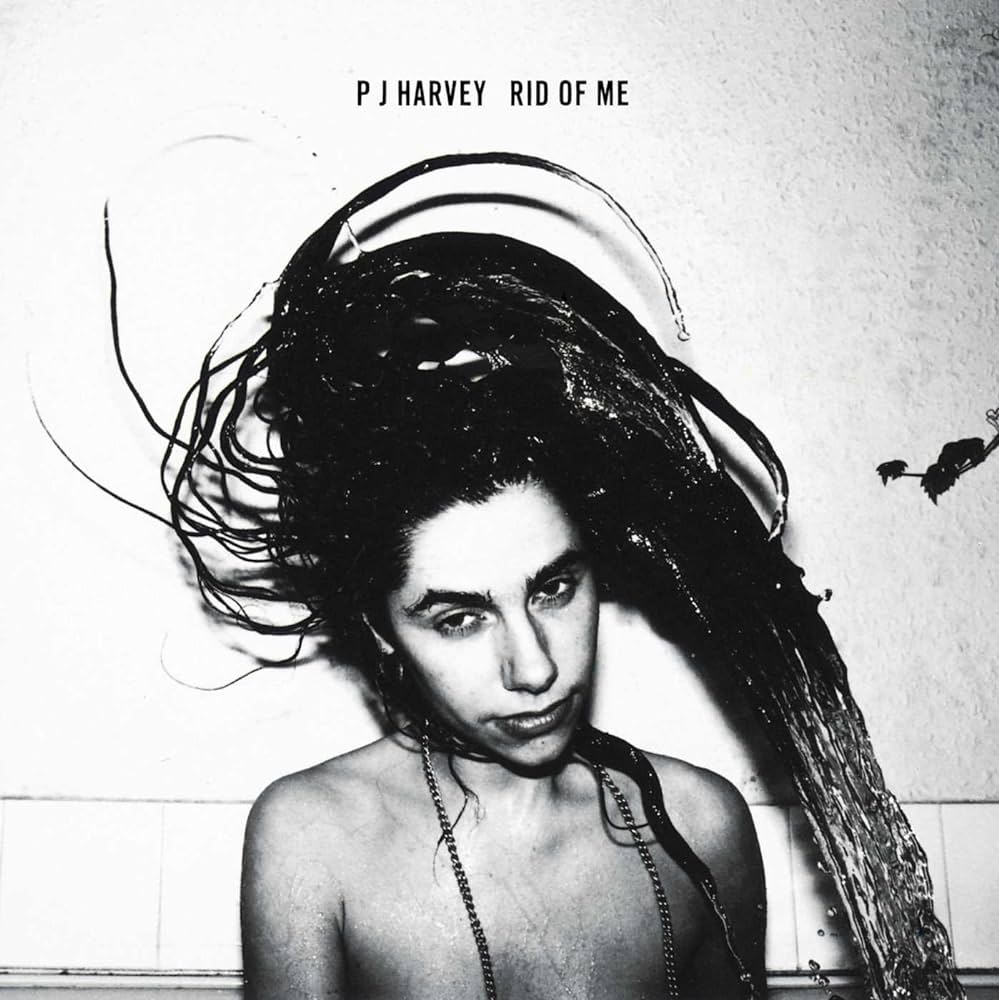

One of Albini’s signature works as a recording engineer was on PJ Harvey’s critically acclaimed 1993 album Rid of me, which valorized a lo-fi aesthetic of raw musical expression, stripped down to its most fundamental elements. In the early 1990s, the emerging subgenre of lo-fi foregrounded debates about both the aesthetic and ideological significance of sound production in rock music. For some lo-fi artists and listeners, modes of performance, recording, and mediation were central to the meaning and expression of the recorded music. The ideologies and impulses of lo-fi were a crucial factor in shaping the contrasting implications of the production myths of Harvey’s recordings of that period, including Rid of me and 4-track demos.

Harvey’s choice of Albini for the recording of Rid of me proved compelling. After all, Harvey’s musical persona had demonstrated a penchant for gendered antagonism and boundary-defying iconoclasm. She also shared similarities in sound and style with Albini’s noise rock aesthetic, namely abrasive guitars, drastic dynamic contrasts, rhythmic complexity, and an emphasis on tight-knit, active ensemble performance.

Read more in “The power of a production myth: PJ Harvey, Steve Albini, and gendered notions of recording fidelity” by Brian Jones (Popular music and society 42/3 (2019) 348–362. [RILM Abstracts of Music Literature 2019-5609]

Steve Albini passed away in Chicago on 7 May 2024.

Below is studio footage featuring Albini and PJ Harvey during the Rid of me studio session in 1993 along with Big Black’s Racer-X.